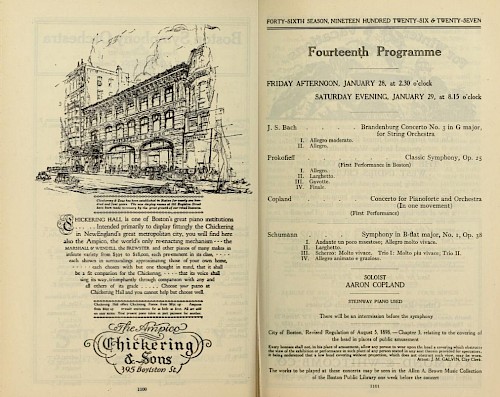

Nearly every commentary on Copland's Piano Concerto—including some of his own—notes its rocky initial reception. Most treat it as an outlier from the composer's short-lived so-called "jazzy" phase; a lesser-known historical curiosity. The work does get performed, as the next installment of Midday Thoughts will detail. But it has not enjoyed the popularity of Copland favorites like Rodeo, Appalachian Spring, and Fanfare for the Common Man, or the Third Symphony, or Old American Songs.

Why not? Much as I want to love everything Copland wrote, it's at least theoretically possible that some pieces are less expertly crafted than others. Perhaps his composer-friends in the 1920s were right: a piano concerto that combined avant-garde dissonance and experimental techniques with popular, syncopated American dance music was a losing proposition, and not even Copland could pull it off. If there was something dated, defective, or sub-par about the Piano Concerto, I wanted to face it.

When I learned that the Piano Concerto would be performed at Tanglewood in July, I determined to go hear it with open ears. It is not a short work; the score indicates an 18-minute duration, though most recordings take faster tempos. In any case, I wanted to know what it would be like to experience the Piano Concerto as a live event, in a concert setting, performed by a large and highly skilled assemblage of musicians, with a large audience on a summer afternoon? How would the music hold my attention over the course of nearly 18 minutes? What can a live hearing of the Piano Concerto offer the twenty-first century listener?

The description below is based on two live hearings at Tanglewood: one at the Friday open rehearsal, and the other at the Sunday concert. The timings given in bold come from the Naxos recording by pianist Ben Pasternack and the Elgin Symphony orchestra conducted by Robert Hanson. Rehearsal numbers from the score (eg. R22) are also given in case any curious readers have access to the score; an online perusal copy from Boosey & Hawkes can be found here.

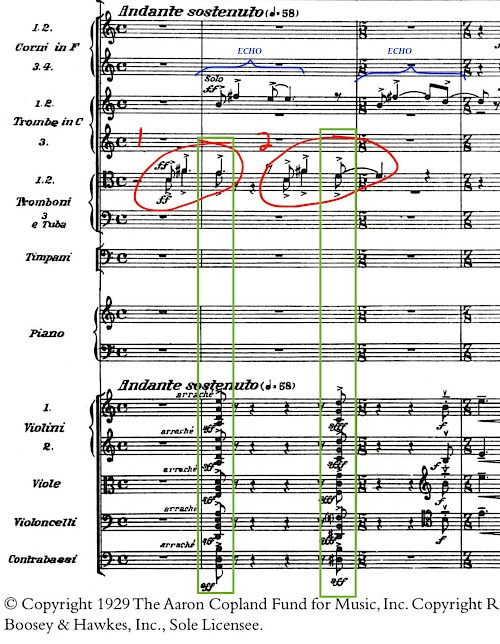

The piece begins with an abrupt upbeat: bup BAAAAH Dum! the brass calls out, punctuated as it falls away by percussive, fortissimo string strikes, and from somewhere within the orchestra an echo sounds (solo trombone, the score tells us). A companion call immediately follows at a slightly different pitch level: bup BAAAH Dah (another pause, with echo).

While the two big sonic gestures are still ringing, shorter versions of the same gesture sound in overlapping succession, like stretto entrances of a fugue (bup BAAH, bup BAAH, bup BAAAH)... These quickly rise in pitch and register, until the accumulated mass breaks like a crashing wave [mvt 1, 0:32] into a thick, foamy chord sparkling with interior motion—voice exchanges like scurrying eddies that propel the energy forward and outward, spreading and enveloping the audience. As the wave recedes, shallow currents rush in from the sides, glistening with blue notes in the flute and clarinet [mvt 1, 0:50-0:56].

The swirls of strings and brass sonorities ebb, replaced by quiet solo piano notes that contrast in both pitch and timbre, remaining like shells or bones left behind on a smooth, water-swept beach [mvt 1, 1:05-1:50]. The ideal pianist has Copland's touch: what Copland in certain scores marked "crystalline," which a friend, pianist Leo Smit, once described as "clarity...with a touch of harshness; and the ability to "convey the intent of his musical thought, without gorgeous tonal quality or brilliant technique," a tone that had a touch of "harshness" (The Complete Copland, 264).

For five more minutes, a bluesy soundscape engages the listener. The orchestra and piano weave an ever-shifting fabric of interlocking melodic material, sometimes sharing, sometimes trading motives and harmonies. The music is an almost impressionist mix of sounds; never is it shocking, but neither is it formulaic, predictable, or even particularly familiar.

Copland's own description of the composition appeared in the program at the premiere. In his prose, jazz, popular music, and the adjective "American" are curiously absent. It reads:

"A short orchestral introduction announces the principal thematic material. The piano enters quietly [R2, mvt 1, 1:04] and improvises around this for a short space, then the principal theme is sung by a flute and clarinet in unison over an accompaniment of muted strings [R4, mvt 1, 2:36]."

The word "improvises" is the only hint of jazz or popular music in Copland's program note, though the work quickly became known as a jazz concerto, a characterization Copland readily used in other contexts when referring to the piece. While he could write music that sounded improvisatory, Copland knew from the outset that he wasn't an improvisor in the jazz mold. In 1928, when he arrived in California to play his "jazzy" concerto at the Hollywood Bowl, reporters and piano movers met him at the train station, expecting him to improvise jazz on the spot for a "publicity stunt." He laughingly but firmly refused. (The Complete Copland, 68).

The note continues:

"This main idea recurs twice during the course of the movement, once in the piano with imitations by the woodwinds and French horns [after R5, mvt 1, 3:40]... and later in triple canon in the strings [R8 & R9, 5:17]...mounting to a sonorous climax [R10 mvt 1, from 6:00]."

This movement is bluesy, vaguely reminiscent of Gershwin's already popular Rhapsody in Blue (1924). It readily fits the 1920s definition of "symphonic jazz," a term Copland used himself.

When the second movement starts, things get a little more raucous, perhaps even offensively so to listeners who may have been lulled or soothed by the first movement. The Concerto was listed at the premiere as being "in one movement," but Copland's note clarified that

"Though played without interruption, the Concerto is really divided into two contrasted parts."

By 1956, with Copland's approval, the Boosey & Hawkes edition used a double bar and a new page with a Roman numeral "II" centered at the top to clearly indicate a new movement.

The solo piano breaks the mood of first movement not at all gently [mvt 2, 0:00]. Harsh, loud, accented, and rhythmically disjointed major seconds seem calculated to give a "wrong note" effect, as if the pianist experiments and corrects himself, or has to dislodge a stuck key. This solo passage is anything but subtle: the term "attacca," traditionally used for a new movement begun without pause, seems especially apt here. Within seconds, the tempo, initially rubato, becomes stricter and accelerates through a descending, dotted-rhythm riff into a section of relative metrical steadiness with plentiful but not disorienting syncopation [R12, mvt 2, 0:28].

"Roughly speaking," according to Copland, this second movement is in "sonata form without recapitulation.

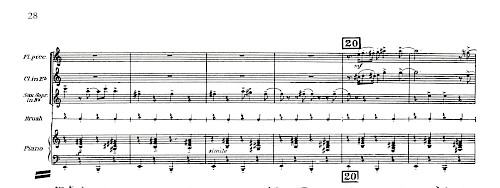

"The first theme [mvt 2, 0:28], announced immediately by the solo piano, is considerably extended and developed before the second idea is introduced by a soprano saxophone [6 bars after R19, mvt 2, 1:51]."

After the "first theme" enters, two full minutes of improvisatory amusement ensue, with piano and orchestra developing parts of the theme. Despite the mixed meters, the underlying pulse remains constant for long enough to prompt some audience toe-tapping. Still, the movement's jarring opening is a recent enough memory that the expectation of any sustained, Gershwin-like dance music has been effectively banished.

With the "second idea" [6 bars after R19, mvt 2, 1:51], we finally hear a memorable, 4 x 4 melody: a descending major triad presented in a jaunty rhythm, extended at the end by a tacked-on stepwise descent from the lowered third scale degree. This respite of tunefulness and metric consistency quickly becomes the exception as the movement speeds onward.

Copland writes:

"The development, based entirely on these two themes, contains a short piano cadenza [after R35, 12:32] presenting difficulties of a rhythmic nature."

But rhythmic complexities are by no means new at this point. By the time the cadenza arrives midway through the 5-minute development section, "rhythmic difficulties" have long been foremost in Copland's grab bag of modernist techniques.

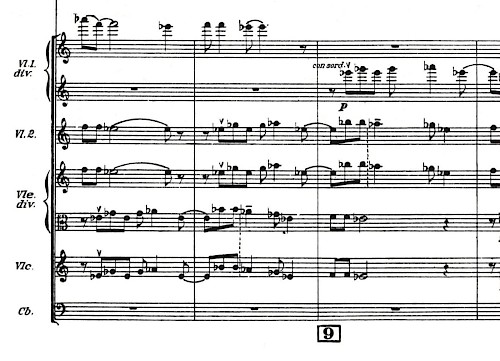

The work's remaining minutes hurtle by at a dizzying pace, with only the barest hints of dance band music fragmented and tossed about. Regular count patterns, balanced periodic phrases, or sustained grooves fail to emerge from the chaos. Often, the piano left hand is out of synch with the right hand, and both are in tension with the orchestra's metrical patterns. In live performance, it is truly a delight to watch the conductor work so hard to hold everything together.

Copland's program note foreshadowed none of the work's boisterous fun or drama for the audience at the premiere. It concludes with two sentences:

"Before the end, a part of the first movement is recalled [R43-46; mvt 2, 7:25]. This is followed by a brief coda [R46-50]."

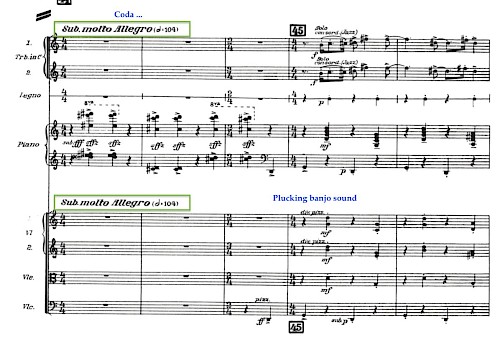

In reality, just before the coda, all hell breaks loose, so to speak: every significant motive of the entire work is superimposed, colliding in a broad-spectrum, fearsomely loud climax, which could be thought of as an ultra-condensed recapitulation. At one point in the coda, Copland's evocation of the banjo—common in jazz before 1930—is unmistakable as he doubles the piano's "oompah" bass-chord pattern with pizzicato strings [R45, mvt 2, 8:35].

The work's final minute employs the full orchestra, including full percussion and brass playing fortissimo. There's a grand pianistic ascent, some tutti chords, a huge pianistic descent, and a dramatic closing gesture that, in effect, reverses the work's opening gesture: instead of bup BAAAH-dum, the brass and strings deliver (da-da-da) BAAAH-bup! and silence drops.

Conclusion

To experience the Piano Concerto is to be carried and tossed by many emotions. The journey is alternately declamatory, atmospheric, jolting, and playful. Does it always make sense? Does each new turn of phrase fulfill the expectations implied by the generic title, by Copland's program note, or by the work’s opening minutes?

I must admit, to me the musical flow doesn't always seem orderly, proper, or inevitable. To pick one moment, I find the solo-piano link between movements puzzling; it may never quite make sense to me dramatically. Other listeners might scratch their heads at different points, as if missing a joke. The Piano Concerto's impact lies in its unpredictable mix of calm and chaos, in the borderline-unhinged kaleidoscopic shifts that lie between its stirring beginning and its abrupt end. It represents Copland’s youthful personality and remarkably mature skill well. It sparks questions, provokes reactions, and ends with dramatic but sudden finality. Facilitated by the new performance materials used at Tanglewood, future performances of this work seem likely to continue to challenge, delight, and entertain ever-increasing numbers of listeners.