Copland's Prelude for Piano Trio is about to step out of the shadows. When he first set the music on staff paper ninety-nine years ago, it was part of a large symphonic work: the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra. The Organ Symphony's high-profile premieres in New York and Boston were Copland's debut on the American orchestral scene. A few years later, he re-wrote the symphony's "prelude" section for smaller groups of instruments. One such arrangement, the Prelude for Piano Trio, languished unperformed for decades. In June 2023, it has been published at last by Boosey & Hawkes.

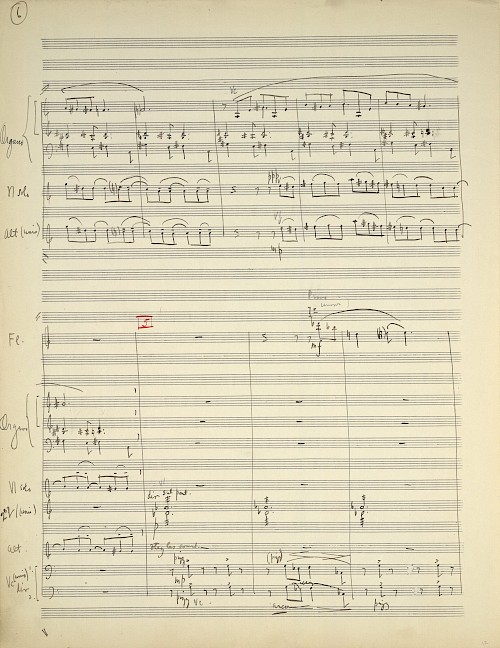

The trio version of Prelude is scored for piano, violin, and cello. The score and parts came to light just before the Copland Centenary in 2000 and were first heard in concert at Yale University that November. The few subsequent performances have used hand-copied materials created years ago by Copland's friend John Kirkpatrick.

Koussevitzky and Kirkpatrick

The story of "Prelude" begins in 1924 when the Russian conductor Serge Koussevitzky was leaving Paris on his way to the U.S., where he was about to become music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He stopped to visit his Parisian friend, the organist Nadia Boulanger, who had recently started a school to train young composers in harmony and counterpoint. Boulanger introduced him to her most promising student, a young Jewish-American named Aaron Copland. Having spent three years under her tutelage, Copland was about to move back to New York City.

Koussevitzky had a brilliant idea. This young American would write a concerto for organ and orchestra and Boulanger would come to Boston to perform the new work with Koussevitzky conducting! With some trepidation, the budding composer got to work. He'd studied orchestration for years, but had never heard an orchestra play a note of his music. By the end of the year, Copland's first full-length orchestral work, the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra, was complete. Walter Damrosch led the world premiere in New York City, and Koussevitzky gave an important second performance in Boston, both starring Boulanger as organ soloist.

Two years later, in 1926, a 21-year-old junior at Princeton named John Kirkpatrick was becoming disaffected with his academic studies. Why not try something different during his last summer of pre-graduation freedom, he thought, before joining his father in business? He signed up for summer music courses near Paris with the famed pedagogue Nadia Boulanger.

Based in New York, Copland was traveling in Europe that year to attend a music festival. He met Kirkpatrick during a visit to Boulanger's studio and the two quickly hit it off. Boulanger had regaled her students with stories of her American performances of Copland's glorious Organ Symphony. Inspired, Kirkpatrick had already made a two-piano arrangement of that work's second movement. No doubt the two new acquaintances played through it for fun, navigating the jaunty, irregular rhythms at a brisk pace.

Kirkpatrick decided on a musical career path and stayed in Europe for further training. But in 1928, his father died and in 1929, the stock market crashed. He returned to the U.S., where he built a reputation as a performer of modern piano repertoire, a music editor, and the first champion of Charles Ives. Copland helped him find freelance jobs as needed. One of those jobs was likely copying the score and parts for Copland's Prelude for Piano Trio.

Copland's aid to Kirkpatrick was mutual. Kirkpatrick was the first person to publish an article about Copland, in the 1928 Fontainebleau Alumni Bulletin. He made a two-piano arrangement of Copland's entire Piano Concerto that was published by Cos Cob Press in 1929. The fourth of Copland's Four Piano Blues, written in 1926, is a miniature dedicated to Kirkpatrick. Titled "with bounce," it is just 70 seconds long.

Kirkpatrick became a renowned scholar and performer of Charles Ives's music, teaching at Cornell and then Yale for many decades. Known for his pioneering performances of Ives's monumental Concord Sonata, he traced his interest in the piece to a music festival Copland organized at the Yaddo artist's colony in 1932.

From Organ Symphony to Piano Trio

The musical content of the Prelude for Piano Trio comes directly from the Organ Symphony—so directly, in fact, that the trio counts as an arrangement rather than a new composition. About 26 minutes long, the Organ Symphony has three movements. The first movement, titled "Prelude," is 6-7 minutes long. The second movement, "Scherzo," is about 8 1/2 minutes long, and the last movement, "Finale," lasts nearly 11 minutes.

Copland figured the Organ Symphony might get more performances if it could be played without the organ. So between 1926 and 1928, he arranged the three-movement work for large orchestra, assigning the organ part to other instruments. The orchestra-without-organ version, technically an arrangement itself, was given the title First Symphony and premiered in Germany in December 1931.

But it didn't stop there. While finishing the First Symphony, Copland decided the first movement, "Prelude," could stand on its own, and created two more arrangements of it: one for piano trio (piano, violin, cello) and the other for chamber orchestra. The two shorter works are both titled Prelude simply because Copland kept the title of the symphonic movement when he re-used the music. The title "Prelude," of course, has roots as ancient as the organ itself. From medieval times it described music that preceded a church service, a pageant, a ballet, an opera, or a longer piece of music. In the hands of later composers like Chopin, Liszt, and Debussy, the prelude became an independent concert piece. Copland's Organ Symphony and First Symphony evoke the older sense of prelude, while the chamber and trio arrangements of just the first movement take on the more recent meaning.

In its chamber orchestra scoring, Copland's Prelude had two early performances—the first in February 1934, conducted by Bernard Herrman, and the second at the Eastman School of Music in April 1935. Boosey & Hawkes engraved and published Prelude for Chamber Orchestra in 1968.

The history of the piano trio version is less clear. No evidence has surfaced of an early public performance, though Vivian Perlis thinks it was probably played, perhaps privately, in the 1920s with either Copland or Kirkpatrick at the piano. She speculates, "It is possible that the piece was tried out by the jazz trio in which Copland played when employed by a hotel in the Pennsylvania Catskills soon after his return from France in 1924. According to him, the guests were 'horror-stricken' by some of the excerpts from the symphony-in-progress that he played for them." (Perlis 2002, pp 59-60) The image of horror-stricken hotel guests is amusing, but Kirkpatrick wouldn't have been involved at that point, for he hadn't yet met Copland or Boulanger. The piece soon faded into the shadows.

The piano trio arrangement next surfaced in 2000 among Kirkpatrick's papers, which are housed at Yale University. It is possible that Copland had simply forgotten about it, but Kirkpatrick saved everything. "[You have] no idea of the pathological extent of my magpiety," he wrote to the Yale archivists when his papers were transferred there in 1980s. The official premiere of the trio occurred at an all-Copland concert given by the Yale Chamber Music Society in November 2000.

The resident ensemble of the Copland House in Peekskill, NY gave the next known performances of the Prelude for Piano Trio. Their 2006 release The Chamber Music of Aaron Copland (Arabesque) presents the piece's only commercial recording to date. Before the decision was made in 2023 to publish Prelude for Piano Trio, it was not available for further performances.

Style and Impact

What impact does Copland's Prelude have on listeners? At the Organ Symphony's 1925 premiere, apparently to mollify the Philharmonic's convention-bound audience, Walter Damrosch infamously remarked from the podium that "if a gifted young man can write a symphony like that at age twenty-three, within five years he will be ready to commit murder." Prelude is the least raucous of the symphony's three movements, but it does bear more similarities to the modernist Igor Stravinsky than to Chopin or Liszt.

Boulanger knew, admired, and taught her students the music of Stravinsky, whose infamous Rite of Spring ballet score had shocked Parisian audiences in 1913. Copland was sometimes called "The American Stravinsky," and he used several techniques in Prelude that were also favored by the modernist composer. Instead of flowing melodies and familiar chord progressions, Prelude features ostinatos—short, repetitious melodic fragments—and themes that are derived not from a standard, seven-note, major or minor scale, but from an "octatonic" scale of alternating whole and half steps (Murchison pp. 48-52).

Today's listeners will not find Prelude shocking or violent, but they may find it mysterious and brooding. Though the notes and rhythms are the same, the Prelude for Piano Trio sounds remarkably different than the Prelude movement from the Organ Symphony, where the sustained, resonant tone colors of the organ add an other-worldly shimmer. Played as a trio, Prelude's tempo is arguably necessarily faster than in its less stripped-down versions. Music from the Copland House plays it at 4:40—nearly 1-½ minutes shorter than Oliver Knussen's chamber orchestra recording; when part of the Organ Symphony or First Symphony, performances can exceed 7 minutes. Played with or without organ, by 3, 16 or 60 musicians, Copland's Prelude is haunting yet appealing, finely crafted and completely Copland. The newly published version for piano, violin, and cello—composed and arranged by Copland himself—will bring this mesmerizing gem to light.

Source list:

- Massey, Drew. John Kirkpatrick, American Music, and the Printed Page. Eastman Studies in Music, 98. Rochester, NY, Boydell & Brewer, 2013.

- Murchison, Gayle. The American Stravinsky: The Style and Aesthetics of Copland's New American Music, the Early Works, 1921-1938. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2013. Accessed 5 May 2023, http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/30248.

- Perlis, Vivian. "Aaron Copland and John Kirkpatrick." In Copland Connotations, ed. Peter Dickinson (Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer, 2002), 57-65.

- Perlis, Vivian and Aaron Copland. The Complete Copland. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013.

- Yale University Library, Finding Aid to The John Kirkpatrick Papers, MSS 56, p. 5. Online at https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/6/resources/10637. See "Additional Description, Biographical / Historical." Accessed 26 May 2023.