Copland's fame rests most broadly on his music. But to those who knew him as a colleague, he was equally famous for his service to the profession. He did far more than contribute masterpieces to the field of American music in the Western art music tradition; he rolled up his sleeves, rallied co-laborers, and cleared land for the field to grow. Composers, directors, conductors, arts administrators, aspiring composers and publishers all knew him as an astute team player, even tempered, and unusually generous with his time and efforts toward improving the prospects for a broad range of American composers.

Surprisingly, the broad, listening public today remains largely unaware of Copland's ongoing, transformative commitment to the compositional community in the U.S. The Wikipedia article on Copland describes his support for other composers only at the end, in a short section subtitled "Critic, writer, teacher." Britannica online barely mentions his activities outside of composing. Sources geared toward musicians, though, are markedly different. In the authoritative music encyclopedia, The New Grove, immediately after Copland's name, dates, and profession are given, the author asserts his importance "as a critic, mentor, advocate and concert organizer" who "played a decisive role in the growth of serious music in the Americas in the 20th century." (Pollack, "Aaron Copland")

A classic music history text now gives his service equal billing to his music, calling him "the most important and central American composer of his generation through his own compositions and his work for the cause of American music [emphasis mine]." Before a single composition is mentioned, the reader learns that Copland "organized concert series and composer groups and promoted works of his predecessors and contemporaries. ... Through encouragement, counsel, and by example, he influenced many younger American composers." (Burkholder, Palisca, and Grout)

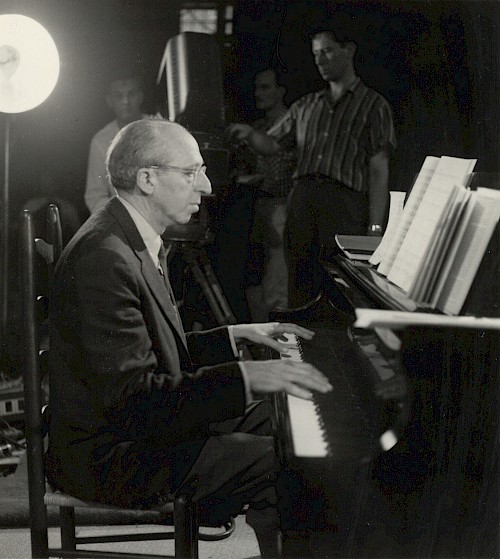

The 1985 film Aaron Copland: A Self-Portrait, is an important exception; of interest to general audiences and seasoned musicians alike, it intertwines the story behind Copland's music with his substantial work in support of American composition as a whole. The 60-minute documentary uses extensive video interviews with Copland himself and other recently departed musical luminaries, among them Leonard Bernstein, William Schuman, Lukas Foss, and Jacob Druckman.

Just how exceptional was Copland's commitment to community-building among composers? Did his efforts wane once he achieved a degree of individual fame? When it came to others' music, how focused were his tastes, his support, his instruction? What seemed to motivate his service to the field? Let’s take a look at comments by Copland, people who worked with him, and other sources to address these questions.

Early career

Even before he found his professional footing, Copland became known as an advocate for other composers. Howard Pollack writes, "Upon returning home from Paris, the 25-year-old Copland not only sought out contemporaries but began befriending and sponsoring younger composers. Such solicitude was remarkable for a composer himself so young and unestablished." (Pollack 1999, pg. 178)

Copland described his early career this way: "When I was in my twenties, I had a consuming interest in what the other composers of my generation were producing. Even before I was acquainted with the names of Roy Harris, Roger Sessions, Walter Piston, and the two Thom(p)sons, I instinctively thought of myself as part of a 'school' of composers. Without the combined effort of a group of men it seemed hardly possible to give the United States a music of its own." (Copland 1960, 164-175)

Almost immediately he joined a new organization in New York City called The League of Composers. One of its founders, Minna Lederman, edited a new and soon-to-be-influential magazine called Modern Music. Interviewed decades later by Vivian Perlis, Lederman recalled being struck by Copland's "tremendous curiosity" about new music, and his outgoing, collaborative nature. "He had a commitment, a deep long-lasting one from his early youth, to the specific American situation," she said. After writing his first article for Modern Music ("George Antheil,” January 1925. The journal was then called The League of Composers’ Review), Lederman said, "he met so many people here and abroad that he became a great, vital contact for us [the magazine's editors]. All at once he seemed to know everyone." (Lederman in Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 47-48)

Lederman and others also remarked on the breadth of Copland's musical interests. Longtime Yale faculty member and Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Jacob Druckman recalled that when he first met Copland in the late 1940s, he viewed the older composer as "a totally establishment person," was inclined to be "suspect of him a little bit" and worried that he would be "unsympathetic" to anything not "neoclassic Americana." Soon Druckman realized "that was not the case at all. He was very erudite and his tastes were catholic...he had a genuine interest in composers of all kinds of music, as well as those working closer to his own style...he had a wonderful eye and ear for the shape of a piece.” (Druckman in Aaron Copland: A Self-Portrait and Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 211-212)

Likewise, William Schuman, ten years Copland's junior, and later the president of the Juilliard school, remembered, "As a teacher, Aaron was extraordinary.... Copland would look at your music and try to understand what you were after. He didn't want to turn you into another Aaron Copland..." (Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 147) Said Minna Lederman: "he had a tremendous curiosity about new music. He would go to more kinds of things that[n] you can imagine. The only other composer anything like that was Elliott Carter in the thirties and early forties.” Copland’s interest, she noted, lasted for three decades. (Lederman in Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 47)

Lederman's magazine reported on international modern music while its sponsoring organization, the League of Composers, put on concerts in New York so the music they wrote about could be heard locally. Copland participated in both. He soon teamed up with composer Roger Sessions to create still more opportunities for performers, audiences and young composers to hear even more new works. The young Copland also participated in the artists' colony called Yaddo in upstate New York; he lived and worked there in 1930 and organized two festivals of modern music there (1932 and 1933).

A Composerly "Merchants' Association"

Copland quickly established a reputation as a team player, though not a malleable one. The composer-critic Virgil Thomson, with whom even Copland himself admitted some degree of rivalry,* gave Copland unqualified praise: "[Aaron] had the great gift of being a good colleague. ... For the first twenty years of Aaron's career as a composer he carried his American colleagues along with him, because he was successful before anybody else. ... he had tact, good business sense about colleagues, and loyalty.” (Thomson in Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 86)

(*Of Thomson, Copland wrote in his autobiography, "We are not much alike in temperament and personality, but we have never had a falling out, even though it has been assumed in the music world that there was terrific competition between us. I doubt either of us would deny this completely, but we could always carry on our friendship and collegial activities.” (Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 85))

Copland and Thomson fully agreed on the benefits of cooperation from the time their careers began in the mid-1920s. Thomson explained, "Aaron and I were sold on the same general idea...We're all members of the same Fifth Avenue Merchants' Association, and our future and our present depend on being good colleagues."

Other professionals recognized that Copland was exceptional in this regard. Biographer Howard Pollack gives the counterexample of composer Roy Harris, who in 1933, "expressed shock over [Copland's] determination to 'hand over the musical destiny of America' to the young. 'Being an Amer-Irishman,' Harris protested, 'I cannot be counted on to have had my say before they nail the lid on.'" (Pollack 1999, pg. 178)

Yet Copland was neither a pushover, nor a martyr to the cause. Publishing executive Sylvia Goldstein put it this way: "He was easy to deal with, but not easily led." (Goldstein in Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 290) William Schuman cautioned that Copland "could be very strong. I never knew him to be mean, and I never knew him to lose his temper... he was a very controlled person, but he did not suffer fools lightly." (Self-Portrait, 22:34) When a crisis in an organization he led conflicted with a compositional deadline, the latter took priority.

1935-1945: The second decade

For the second decade of his career, from 1935, Copland's community building continued apace. Some of it was very public: he was a founding teacher at Tanglewood Music Center, the summer music school which opened in 1940, led by Copland's friend and champion, conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who had recently claimed the location in the Berkshires as the summer home for the Boston Symphony Orchestra. (Self-Portrait, 42:49)

Much of Copland's community building was visible mainly within the music profession. By the late 1930s, new American compositions and smaller publishing ventures had proliferated, but significant barriers to performances remained. Composer Otto Leuning explained, "creative musicians in the United States were having desperate difficulty bringing their music before the public. ... even people in the music profession seldom knew where to find it when they wanted to." (AMC Solicitation Letter, May 15, 1962)

To address the problem, Copland and Leuning assembled a coalition of six composers with connections to existing music publishers. After months of discussion and negotiation, they met in Copland's loft in 1939 and signed articles of incorporation for the American Music Center; a non-profit that supported American composers and contemporary music until it merged with Meet the Composer in 2011 to become New Music USA. He presided over the organization from 1939 until 1945 and continued to advise its activities for decades afterward.

Other aid to young composers happened behind the scenes. In one case (Pollack 1999, pg. 178) the 38-year-old Copland happened to meet a 28-year-old German emigre composer who was copying his own orchestral parts in a public library—a thankless and time-consuming task. Copland quietly paid for a professional copyist to do the work instead. After the Tanglewood summer music school opened, Copland quietly assumed the role of talent scout for Koussevitzky. (Leonard Burkat in Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 206)

Informal gatherings at Copland's loft in Manhattan were frequent in the 1930s and 1940s. The pianist Leo Smit, who later recorded Copland's complete piano works, recalls one gathering at Copland's loft around 1941. "David Diamond played, and Harold Shapero, Elliott Carter, and Oliver Smith were there—quite a gathering of New York's finest. I played the curtain raiser—a piano transcription of a recently composed orchestral work of my own. Aaron took pleasure in introducing new talent—he was always on the lookout." (Smit in Copland/Perlis 2013, pg. 264)

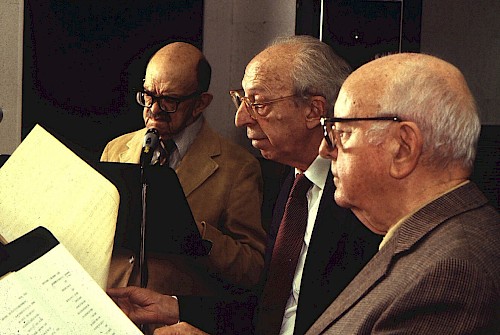

Schuman and composer David Diamond recalled those days in an interview from the 1980s. In the interview, Diamond also mentions an early music publishing venture Copland was involved with before the American Music Center: the Arrow Music Press, previously known as Cos Cob Press. (Self-Portrait, 24:05)

After World War II

Copland's assistance to other composers only increased after World War II. It is true that Copland's overtly nationalist impulses did wane in the late 1940s (read more about that in a recent Midday Thoughts here). But his community building activity increased substantially through the 1960s and into the 1970s, even as his own drive to compose faded. His personal business papers for the American Music Center, the Arrow Music Press, and other similar organizations fill hundreds of folders at the Library of Congress archives, attesting to Copland's hands-on logistical support of American composition and its performance. The archives hold hundreds more pages of correspondence with other composers throughout the range of his career.

As his health began to fail, Copland arranged with his attorney to start what is now The Aaron Copland Fund for Music, a foundation that would continue to support composers and the performance of contemporary music after his death. In Aaron Copland: A Self-Portrait, Jacob Druckman, who later became the first president of the Aaron Copland Fund for Music, summarizes Copland's vast influence on future generations. Druckman and his peers, who came of age after World War II, were less influenced by Copland's musical style than by his "example, particularly in the kind of citizen that he was in the world of music—shouldering of responsibility and not being out for his own personal glory and gain. He felt as though the advancement of the art was his responsibility." Druckman continued, "Aaron was the kind of person who goes out and creates something that was not there, who invents festivals, invents occasions, invents ways to help young composers." (Self-Portrait, 24:38)

To the extent that today's composers and audiences hear more new music with the Copland Fund's assistance than they would have otherwise, Copland's support for American music continues.

Sources & Further Reading

- "Aaron Copland". Wikipedia. Accessed 21 April 2023.

- American Music Center’s Solicitation Letter of May 15, 1962, signed by Aaron Copland, Howard Hanson, Otto Luening and Quincy Porter. A “Virtual Séance” with the Founders of the American Music Center. NewMusicBox. Accessed 13 March 2023

- Burkholder, Peter, Claude Palisca and Donald J. Grout. “Aaron Copland” in A History of Western Music, 10th ed. (New York and London: W. W. Norton, 2019), 893-895.

- Copland, Aaron, "The New 'School' of American Composers," The New York Times Magazine, March 14, 1948, section 6, 18. Reprinted as "1949: The New 'School' of American Composers" in Copland on Music (Garden City, NY: Doubleday: 1960), 164-175.

- Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. The Complete Copland. (New York: Pendragon Press, 2013), 48, 85, 147, 206, 290.

- Perlis, Vivian and Ruth Leon, Aaron Copland: A Self-Portrait. Films for the Humanities & Sciences. Princeton, NJ. Online Video, English, [2007], ©1985

- Machlis, Joseph. "Aaron Copland." Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed 11 February 2023.

- Pollack, Howard, "Aaron Copland," Grove Music Online, accessed 25 February 2020.

- Pollack, Howard. Aaron Copland: The Life & Work of an Uncommon Man. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1999), 178.