In his autobiography Break Shot: My First 21 Years, James Taylor describes the diverse musical influences of his youth. “As a kid I was very influenced by my parent’s record collection…Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copland had a BIG effect on my harmonic sense.”

A composer-acquaintance brought this comment to my attention. Since I just published a study of Appalachian Spring, this piqued my curiosity. The composer herself, Alex Shapiro, has had a successful career scoring for television and film and has since returned to her roots as a concert music composer. She is a big believer in Americans opening their ears and incorporating diverse musical influences. This got me thinking about Copland and his own bent toward incorporating diverse musical influences. This post is called Crossover Copland in the spirit of exploring the ways Copland and his music have crossed genre boundaries.

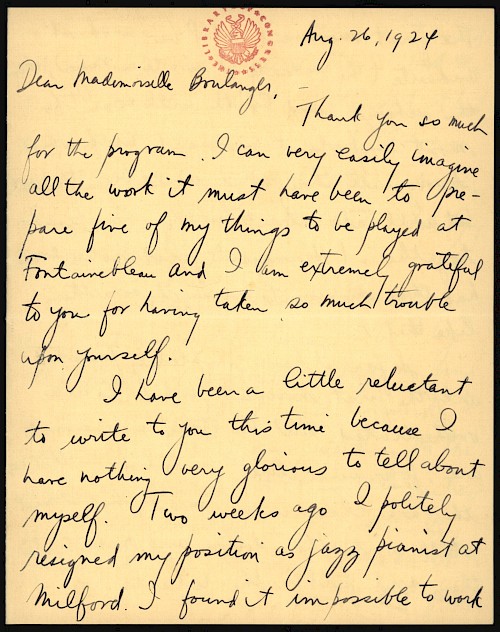

Copland was a composer who employed musical crossover. This dated from (at least) his three years of European training with the famed composition teacher Nadia Boulanger in Paris. She instilled in Copland the imperative to bring his American voice into the contemporary classical music he sought to write. For a Brooklyn boy like Copland, that meant Tin Pan Alley dance-band music, which he played for income in Brooklyn and at summer resorts north of the city from his late teen years into his twenties.1,2 Music for the Theatre and the Piano Concerto were two works that reveal those influences, the former in its quotation of “Sidewalks of New York” (the famous lines “East Side, West Side”) and the latter more obliquely, in the syncopated rhythms of its tone clusters and the thick chords and blue notes of the first movement.

But what exactly was Copland “crossing over”? The term itself implies a border, a boundary, a line between distinct categories. Copland lived amidst categories that were cultural, musical, and socioeconomic. The identity categories of today also operated to some extent 100 years ago: Copland was Jewish, gay, musically gifted, and a first-generation American. His musical world was defined by institutional categories: Western Art music (supported by institutions including symphony orchestras, concert halls, colleges, conservatories, and universities) and popular, commercial, or functional music. Later in life, he described the musical categories this way:

“I grew up . . . in an environment that had little or no connection with serious music . . . music and the life about me did not touch. Music was like the inside of a great building that shut out the street noises.” He described his desire to be like the great European composers. “To set oneself up as a rival of the masters: what a daring and unheard-of project for a Brooklyn youth!"3

The lack of similar interests in his family and schoolmates apparently reinforced the idea that art music was separate from society: a special place of beauty or fascination.

When Copland used jazzy idioms in his early works, he was crossing between his chosen field as a composer and his everyday life as a boy from Brooklyn. Boulanger’s encouragement—and Copland’s subsequent travels—expanded the geographic range of his everyday life far beyond Brooklyn, to vistas across the United States and Latin America.4,5 Claiming the American West and the American past as part of his everyday life, Copland continued to cross boundaries of time and place. He incorporated cowboy songs into Billy The Kid, the fiddle tune “Bonaparte’s Retreat” into “Hoe-Down” from Rodeo, and the Shaker melody “Simple Gifts” into Appalachian Spring.

Those two last cases illustrate that Copland’s music could cross in two directions. Copland brought everyday tunes into the concert hall, and after a while, the Copland version traveled back from the concert hall into everyday life. “Bonaparte’s Retreat” is now known as “Copland’s” in some corners of the fiddling world. Similarly, thanks to Appalachian Spring’s popularity, “Simple Gifts” has spread far beyond its Shaker origins to become a popular English-language Christian folk hymn, “Lord of the Dance,” and a staple of the Irish-themed Riverdance franchise.

Copland the composer often crossed between the socio-economic-musical categories of “classical” and “popular” music. The classical tradition he sought to join as a young American drew a sharp distinction between music with broad commercial appeal (sometimes referred to as entertainment or functional music) and what purists considered serious art music (mostly chamber and symphonic, rooted in the 19th-century European ideal of “absolute” music). Some of Copland’s composer-peers worried that he was selling out when he started composing film scores for Hollywood. But only a cynic could claim Copland’s sole motivation was financial. He enjoyed the challenge of writing music to order and appreciated the intricacies of the film industry. With one notable exception he found the process musically rewarding and published thoughtful articles on the subject.6

Also encouraging Copland to cross over was the Depression-Era, Popular Front-informed push to make art for the masses.7 This movement in America had political support from Soviet Communists, but support also came from an all-American, grass-roots, anti-intellectual mindset that judged a composer’s worth by his economic success. In one sense, all of Copland’s stage works, including the ballets, incidental music, puppet shows, etc., crossed between the realms of serious music and functional music. Works written for patriotic occasions (Fanfare for the Common Man, Lincoln Portrait, Preamble for a Solemn Occasion), choruses (What Do We Plant?, An Immorality) and children’s pieces (Sunday Afternoon Music, The Young Pioneers, The Second Hurricane) can be considered a type of crossover on Copland’s part.

Long after Copland’s death, his music continues to cross over. "Hoe-Down," Fanfare for the Common Man, and Appalachian Spring appear often in underscoring and arrangements. Each season, dozens of high school marching bands arrange a surprising array of Copland works, popular and obscure, for their own combinations of instruments: Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid excerpts, “Hoe-Down,” “Long Time Ago,” movie score excerpts. From the 1990s onward, The National Cattlemen's Beef Council has used “Hoe-Down” in advertising campaigns. Crossover violinist David Garrett has released an arrangement of “Hoe-Down” with rock band and orchestra.

Fanfare for the Common Man has crossed into popular culture so thoroughly that some people think it’s public domain. It has underscored promotional videos for nearly every branch of the U.S. military. Rock bands including Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, Mannheim Steamroller, and the Rolling Stones have recorded and arranged it. It has crossed national boundaries as a signature theme for the 1984 summer Olympics. A June 30, 2016 performance at the Hungarian State Opera House in Budapest by the orchestra and chorus of the Hungarian State Opera, six vocalists, a five-piece rock band, and a jazz choir became a PBS Rocktopia broadcast released on DVD.

Appalachian Spring, meanwhile, can be heard at museums and memorial sites, in stores and restaurants, elevators and boardrooms. It has been a soundtrack for times of national mourning, as on the first anniversary of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks (HBO, 2002), and after the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Celebrations and histories of the Hubble telescope, the U.S. Capitol, and the National Park Service (a Ken Burns film) have used it as underscoring.

One of the more fascinating crossover uses of Copland’s music is in He Got Game, the 1998 Spike Lee movie about basketball. The score uses no fewer than fifteen different orchestral works by Copland alongside (but never overlapping with) music by Public Enemy. “When I listen to Copland’s music, I hear America, and basketball is America. It’s like he wrote the score for this film,” said Lee.8,9

James Taylor probably knew the Appalachian Spring Suite from one of several LPs issued before 1962. Since his family of origin had strong ties to Boston, his parents may have owned Serge Koussevitzky’s 1946 recording with the Boston Symphony, either on 78s or the LP reissue or the same orchestra’s newer recording led by Copland himself. A 1956 Columbia label release (Ormandy, Philadelphia) would have included a rarely heard, seven-minute section of dark, turbulent music interrupting the “Simple Gifts” variations.

Tracing the specific imprints of Copland’s harmonic vocabulary on Taylor’s music is a project for another day. But both Aaron Copland and James Taylor spent careers creating works that incorporated their own diverse musical influences, gleaned from their experiences as Americans both at home and abroad, with the goal of creating music that reaches many listeners. Their personal values, like their music, support diverse, crossover musical expression as a basic American trait.

Jennifer DeLapp-Birkett is a musicologist based in Ithaca, New York. Beginning with her award-winning dissertation Copland in the Fifties: Music and Ideology in the McCarthy Era (University of Michigan, 1997), she has contributed substantially to Copland scholarship with many conference papers and publications, most recently as co-editor of a critical edition of Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring, Original Ballet Version (A-R editions, 2020).

For Further Reading

- Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. The Complete Copland. (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013): 15.

- Pollack, Howard. Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. (New York: Henry Holt, 1999): 39.

- Copland, Aaron. Music and Imagination (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952): 98.

- Levy, Beth. Frontier Figures: American Music and the Mythology of the American West. California Studies in 20th-Century Music Series. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

- Hess, Carol. “Copland in Argentina: Pan Americanist Politics, Folklore, and the Crisis of Modern Music.” Journal of the American Musicological Society, 66, No. 1, (2013), 191–250.

- Bick, Sally. Unsettled Scores: Politics, Hollywood, and the Film Music of Aaron Copland and Hanns Eisler (United States: University of Illinois Press, 2019)

- Crist, Elizabeth Bergman. Music for the Common Man: Aaron Copland during the Depression and War . New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Sterritt, David. “Spike Lee Chooses Copland Classics for Soundtrack.” Christian Science Monitor, May 8, 1998, 15.

- Gabbard, Krin. “Race and Reappropriation: Spike Lee Meets Aaron Copland.” In Postmodern Music/Postmodern Thought, ed. Joseph Auner and Judith Lochhead. London: Routledge, 2002.