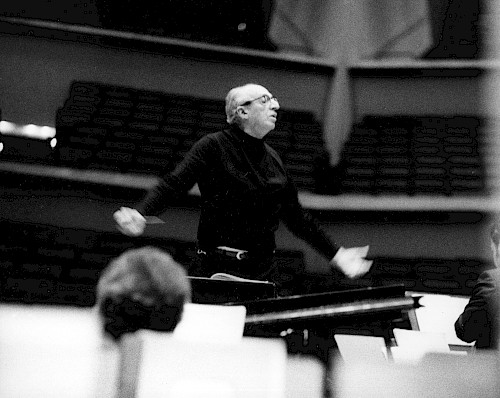

On June 16, 1982, the New York City Center had a rare and wonderful evening planned. The Martha Graham Dance Company was engaged to perform the Appalachian Spring ballet, and the composer himself had agreed to conduct. Copland had become a seasoned conductor in the thirty-plus years since the ballet's premiere. The dancers and musicians knew their parts thoroughly, as they performed it regularly with the Graham Company music director Stanley Sussman conducting. Copland would step in at the dress rehearsal that afternoon for a run-through before the evening performance.

And yet...an edition emergency was brewing. Vivian Perlis, who was present that day, remembered it well. At the rehearsal, she wrote, "conductor Stanley Sussman turned the podium over to Copland, the orchestra members welcomed the composer warmly, and the dancers stood poised to begin. Copland opened his score and picked up his baton... [but] soon it was clear something was amiss." (Complete Copland 179-180). Of course, Copland knew the music better than anyone—but his conducting score didn't match what the musicians were playing, and it didn't fit the choreography!

Emergency Editing

Copland's assistant, the composer David Walker, came to the rescue. In the few hours before the curtain rose, he went through all 985 measures of Sussman's score and "marked changes in red pencil into Copland's score," writes Perlis. A marked-up, ad hoc performance edition was all Copland needed. The show went on, with the audience none the wiser.

How could such a near disaster occur? Copland had conducted the *suite* for Appalachian Spring many times. But he never would have expected the much shorter suite to work with the choreography. Less than 10 years earlier, in May 1973 at Columbia Records' 30th Street studios, Copland had conducted a version of Appalachian Spring for Columbia Masterworks that combined the suite with a handwritten insert that reintroduced the longest section of music he had cut from the ballet when creating the suite.

What must have been forgotten was the fact that many other differences remained between the suite and the complete ballet, so the 1973 recording probably shouldn't have been called "First Recording of the Original Version" on the cover. We don't know for certain, but it's possible that Copland tried to use that score at the dress rehearsal.

The problem of the differing versions had first surfaced almost 30 years earlier, when conductor Eugene Ormandy had to abandon his plan to have the full Philadelphia Orchestra play for a Graham Company performance in 1954. At the time of the City Center performance, the original, choreographic version of the ballet score was still unpublished. Apparently even Copland lost track of how many distinct versions of the score existed, all of them sharing the title Appalachian Spring.

Asked about it many years later, Copland remarked, “When you are working on a piece, you don’t think it might have use past the immediate purpose for its composition, and you certainly don’t consider its lasting power: You are so relieved just to have it finished for the premiere!” (Complete Copland, 174)

For nearly 70 years, many exceptionally fine musicians and scholars had an incomplete picture of the different scores for Appalachian Spring, including Copland and his assistants, publishers, major classical record labels, musicologists, and many conductors. The ideal situation for a scholarly edition!

In 2013, after Graham's choreography was released for licensing by other dance companies, it became a priority to reconcile the various editions. Through the combined efforts of Boosey & Hawkes, the Aaron Copland Fund for Music, and the conductor Aaron Sherber, who was then the Graham Company's music director, Philip Rothman created two new performance editions of Appalachian Spring that *did* match the Graham choreography.

The new 13-instrument engraving became the basis for an award-winning scholarly edition called Appalachian Spring: Original Ballet Version, which was published in 2020 as part of the 40-volume series Music in the United States of America (MUSA). The MUSA project, housed at the University of Michigan and funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and two pre-eminent scholarly societies, the American Musicological Society (AMS) and the Society for American Music (SAM), is "designed to reflect the richness and diversity of our nation’s heritage."

Critical or Scholarly Editions

If performance editions are tools for performers, scholarly editions—also known as critical editions—are for historians, analysts, and performers who want the back story; anyone who wants to know more about the composer's intentions, or wishes to make their own informed decisions about exactly which notes to play, and how to play them.

As the experienced music editor Mark Clague describes it, "[A critical edition] differs from a standard [performance] edition or anthology mainly because the critical edition explains the choices made in its creation. Standard editions present a text but fail to explain the many and inevitable decisions made by editors. With essays, editorial policy statements and explanatory notes, the critical edition invites users to understand the artistry of authors more deeply. ... [It] combines the best of historical research with the best of editorial accuracy and tradition to produce an edition that represents the authors’ work in as definitive a form as possible." (https://smtd.umich.edu/ami/gershwin/?page_id=43 accessed 2/13/2024)

Let's break down the features of a critical edition using the Appalachian Spring MUSA volume as an example.

Features of a Critical Edition

The Preface

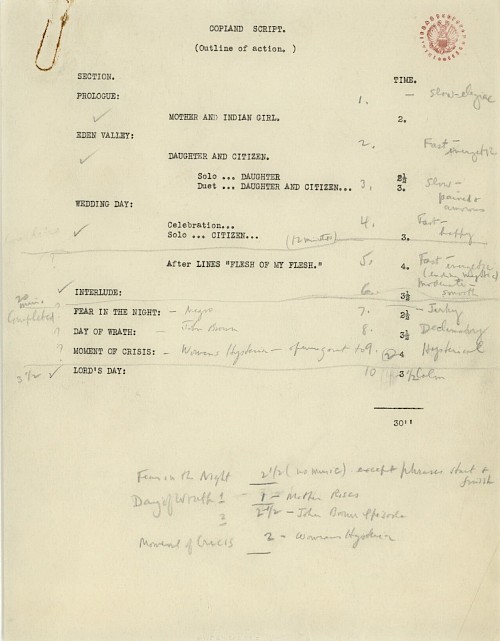

If the opening paragraphs describing the incident at the New York City Center confused or intrigued you, the 2020 critical edition of Appalachian Spring will set everything straight. The “introduction” or “preface” to a critical edition, usually written by scholars, presents the historical background and significance of the music and its composer(s), and addresses any mysteries that required editorial sleuthing. In its 50-page preface, "Appalachian Spring: The Score for Graham's Ballet" retells the story of Appalachian Spring's genesis, using both original documents and secondary sources. Next, the preface describes how Copland built a thirty-minute composition to suit Graham's script using the now-famous Shaker tune "Simple Gifts."

It's the third section of the preface, "Appalachian Spring after the Premiere," that unravels the bigger mystery: how the ballet gave birth to a suite, which in turn took on a third, hybrid identity—leading to a fourth and a fifth version, both of which could expand or contract to meet a conductor's desires. The Preface closes by reflecting on "the identity and limits of a critical edition." The preface's source list takes up five pages at the back of the volume. All this in 22,000 words—far shorter than most detective novels.

The Notated Score...and More

Normally, the score comes next. For the Appalachian Spring edition, we editors decided that representing Graham's choreography on the pages of the score would help readers understand how intertwined were Copland's original music and Graham's concept. After considering many options, Aaron Sherber and I chose to use still images from a video recording of Graham herself dancing the main role. On every page of the score but the first, two still images appear, for a total of about 350 images. In true critical edition fashion, our rationale and image selection process are spelled out in the Critical Report that follows.

The Critical Report

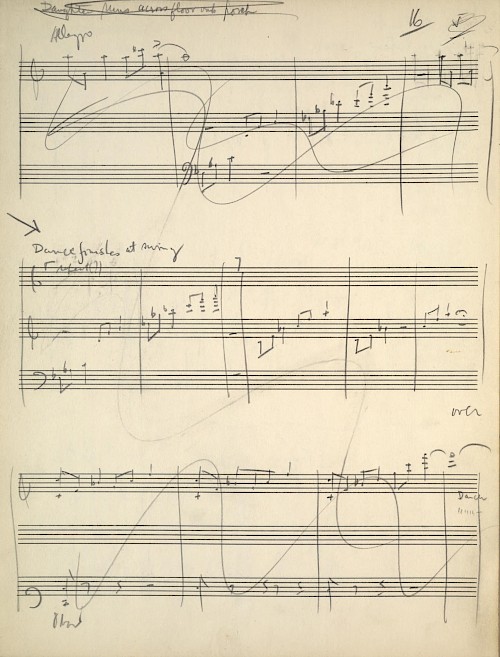

A "critical report" normally appears after the score. First, every source the editors consulted when making notation-related decisions is listed and described. In the case of Appalachian Spring, some sources are hand written: annotated scripts by Graham, sketches and manuscripts by Copland; other sources were published scores with markings. Two recordings and two films of the ballet were also consulted. Next, a statement of "editorial methods" makes explicit exactly how decisions were made. Which sources were regarded as the most definitive when discrepancies arose?

Thirteen pages of "critical commentary" follow, presented in one multi-page chart that describes every single editorial decision, however minute. The location of the contested musical event is indicated by measure number, then the beat within that measure, and usually the instrument(s) playing. For example: in measure 922-925 of Appalachian Spring, dynamic markings were missing from Copland's manuscript score, but were included in the critical edition because they were marked into two later, often-used scores.

Though detailed and highly technical, these charts provide a nuts-and-bolts-level user's manual for the conductor, allowing him or her to make specific and well-informed musical decisions and to communicate any changes to all the performers. The goal, of course, is to ensure that everyone is following exactly the same notated plan—well in advance of the dress rehearsal!

Optional Features

In addition to the preface, the score, and the critical report, as well as the expected acknowledgements and bibliography, other features are possible. For the Appalachian Spring MUSA edition, twelve photographic plates appear between the preface and the score itself. These include some of Copland's handwritten sketches, a page from Graham's script, and a table Copland made when attempting to sort out the versions. One color image shows a page from Stanley Sussman's score with years of accumulated conductors' markings. Within the preface are useful tables that give the dates each version was composed, performed, and published. Another set of diagrams compares the structural differences between the most popular versions.

Another optional feature, appendices, offer answers to three additional questions. What tempos best match the Graham Company choreography? In Appendix 1, Aaron Sherber reports tempo measurements taken from select archival recordings. Second, when auditorium space and budget allowed for more than thirteen instruments, how has the Graham company enlarged the ensemble? Appendix 2 gives the instrumental doublings that they used, with Copland's permission. Finally, what hybrid versions now circulate on commercial recordings, and exactly which score versions did the conductors use? Appendix 3 provides detailed answers.

Future Copland Editions?

Many of Copland's works are excellent candidates for a scholarly edition. As with Verdi's operas, the more branches of the arts involved (stage, screen, dance), the more adaptable the final artistic product tends to be, making it harder to pinpoint a single, fixed score that represents the composer's intention. For Copland, such collaborative works include film scores, ballets, operas, and incidental music. Even for straightforward, unambiguous Copland favorites, performers and scholars would benefit from an edition that includes facsimiles and other images, performance history, and other elements of a "critical report." And although performances are currently not permitted, Copland's student works, withdrawn compositions, incomplete works, and sketches could be of great interest to students and scholars.

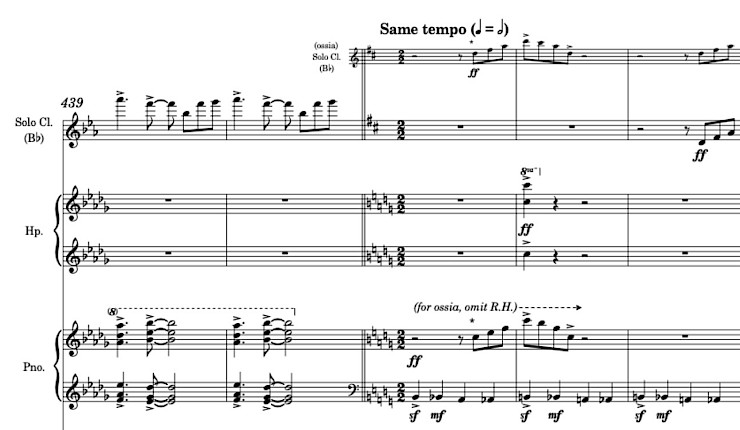

As I mentioned in Editing Copland, Part 1, some editions blend features of a performance edition and a scholarly edition. Rothman's new engraving of the Clarinet Concerto is one example. It includes several pages of historical background that describe Benny Goodman's request that Copland lower the highest pitches, and explains the Copland estate's decision to include notation for the original, higher version as an ossia (an option) alongside the final version that Goodman eventually premiered. Similarly, the Third Symphony performance edition includes notation that allows an orchestra to perform either Copland's original ending, or Bernstein's shortened version; a preface explains the differences and cites published scholarship, giving the reader further opportunity to research the matter. Four pages of introductory material in the performance edition of Appalachian Spring Ballet for Full Orchestra briefly explain the different versions and David Newman's role in re-orchestrating certain passages to create a score that suited Graham's choreography.

The inclusion in the published score of the "critical apparatus"—the features described above—is what differentiates a critical or scholarly edition from a performance edition. However, it must be noted that editors of performance editions use many of the same tools and methods. For example, the last figure in Rothman's article on his performance edition of Rodeo shows that complex, detailed charts akin to those in the Appalachian Spring critical edition lie behind the notation that performers see on the page when they perform Rodeo. Ultimately, "scholarly edition" is probably a more precise term than "critical edition," since, as James Grier points out, all editors use critical methods to make decisions.

Behind every published Copland score lie myriad, detailed editorial choices. The path from any composer's musical idea to sound waves produced by performers can be complex indeed. Whether the end product is a performance edition, a scholarly edition, or something in between, music editors and the notated scores they produce have important roles to play.

Sources & Further Reading

- Copland, Aaron. Concerto for Clarinet and String Orchestra with Harp and Piano with ossias from the 1948 manuscript version. Musical score. London: Boosey & Hawkes, 1952. Second printing: August 2013. Third printing with formatting upgrades: May 2014. New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 2014.

- Copland, Aaron. Third Symphony. Musical score. London: Boosey & Hawkes, 1947. Second printing 1966. Third printing with new engraving by Philip Rothman (December 2014). Corrected July 2017. New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 2017.

- Copland, Aaron. What to Listen for in Music. Rev. ed. New York: McGraw–Hill, 1957.

- Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. The Complete Copland. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013.

- Copland, Aaron. Appalachian Spring: Ballet in One Act for Full Orchestra. Musical score. New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 2016.

- Copland, Aaron. Appalachian Spring: Ballet in One Act for Thirteen Instruments. Musical score. New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 2020.

- DeLapp-Birkett, Jennifer and Aaron Sherber, eds. Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring (Original Version). Music in the United States of America (MUSA), vol. 31. Middleton, Wisconsin: Published for the American Musicological Society by A-R Editions, Inc. 2020.

- Grier, James. The Critical Editing of Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Perlis, Vivian and Philip Rothman. "Editors' Notes" to Aaron Copland, Concerto for Clarinet and String Orchestra (New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 2014), pp. [iii-vi].

- Pollack, Howard. Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. Bloomington, Ill: University of Illinois Press, 2000. First printing: New York: Henry Holt, 1999.

- Rothman, Philip. "Notes" to Aaron Copland, Third Symphony (New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 2017), p. [iii].

- Sherber, Aaron. "Notes on This Edition." In Aaron Copland, Appalachian Spring: Ballet for Orchestra. (New York: Boosey & Hawkes, 2016) pp. [ii-iv].

- Wallace, Helen. Boosey & Hawkes: The Publishing Story. London: Boosey & Hawkes, 2007. See pp. 17-18 on Copland’s contract with Boosey & Hawkes.