My June article announced the first publication of Copland's Prelude for Piano Trio. This short piece, for violin, cello and piano, is Copland's own arrangement of the first movement of his 1924 Symphony for Organ and Orchestra. The manuscript had lain forgotten for five decades in the papers of pianist and scholar John Kirkpatrick, a longtime friend of Copland. After it came to light in the late 1990s, it was premiered in 2000 but remained in the shadows.

As the rights holder of Copland's intellectual property, the Aaron Copland Fund for Music has considerable discretion about where, how, and how much of his unpublished music gets printed and performed. Many manuscripts remain unpublished for good reason. Some are incomplete sketches. Some are fragments or drafts that he later developed into a different, more polished score. Others he considered "juvenilia:" assignments or exploratory student exercises which, in his estimation, didn't represent his individual voice.

Some music was performed once for a specific purpose (like The World of Nick Adams), and Copland decided it either wasn't worth repeating or didn't stand well on its own. Still other works (like Cortège Macabre) are "withdrawn:" though they may have circulated for a time, Copland expressed the clear desire that they not be performed or distributed further. Often, as is the case with Grohg, this is because he essentially disassembled it and used it for parts.

None of these red flags appeared for Prelude for Piano Trio. Once the Copland Fund confirmed that the trio version was musically identical to the first movements of the Organ Symphony and the First Symphony, and that Copland had also fully approved the publication of his 1934 chamber orchestra arrangement of the Prelude movement alone, the trio arrangement got a green light. Philip Rothman engraved it, and Boosey & Hawkes offered it for sale beginning in June.

Lingering Questions

The "OK to publish?" question was answered, but others remained. When and why did Copland first make the trio arrangement? Why and when did he give it to Kirkpatrick? Was it ever performed? And why didn't Copland get it back? Vivian Perlis had addressed the "why Kirkpatrick" question in a November 2000 talk at the Library of Congress, published later in 2002. The two were friends who collaborated frequently; Kirkpatrick was a good copyist who needed work.

The "when" questions are trickier. I began with a table of dates for the four published versions of the Prelude movement.

Title | Finished | Premiered | Published |

|---|---|---|---|

Symphony for Organ and Orchestra

| 1924 | Jan 1925, NY | 1963 |

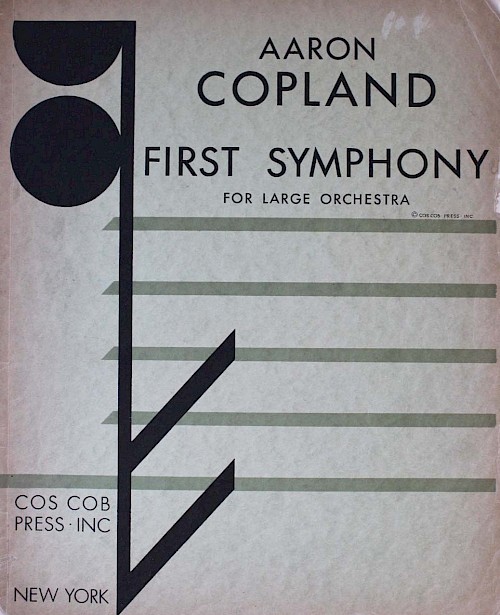

First Symphony for Large Orchestra

| 1928 | 1926 (scherzo only) | 1931 |

Prelude for Chamber Orchestra | 1934 | 1934 | 1968 |

Prelude for Piano Trio | ??? | 2000 | 2023 |

"Four scorings of Prelude" by Jennifer DeLapp-Birkett, October 2023.

Perlis could find no definitive date for the completion of the piano trio. Copland could have made the arrangement while he was still writing the Organ Symphony. He first learned of Kirkpatrick's financial woes in 1929, making that a possible starting point for the trio project. Ultimately, she concludes, "It is unclear which came first: the chamber orchestra version or the trio arrangement." If the trio came second, then 1934 is its earliest possible date.

Has any new information emerged in the last twenty years, I wondered? Perhaps the details of Kirkpatrick's activities or whereabouts in the 1920s and 1930s would eliminate certain dates. From Drew Massey's 2013 biography of Kirkpatrick, I gleaned two useful tidbits.

First, although they met in 1926, Kirkpatrick and Copland didn't live in the same city until 1931. They didn't correspond about the Piano Trio. If Copland's trio arrangement dates from 1924, then he must have dug it out years later to give to Kirkpatrick. From 1931 through 1947, they had ample opportunities to exchange materials in person.

Second, I learned from Massey that Kirkpatrick helped organize dozens of concert series in Connecticut in the 1930s and 1940s. This wasn't an answer, but it raised good questions. Did Kirkpatrick ever program, or consider programming, the Prelude for Piano Trio in Connecticut? Are the programs, publicity, or administrative papers for those series available for examination? Another lead that I have yet to follow.

Meanwhile, since very little is written about the Prelude for Piano Trio itself, I continued to comb the literature on the other three published versions, hoping to find bits of relevant information.

The Prelude for Chamber Orchestra was particularly intriguing. It was the only other instance of Copland arranging the Prelude movement as a stand-alone piece. The manuscript is in Rochester, New York, at the Eastman School of Music, not at the Library of Congress like most of Copland's scores. Why did both manuscript arrangements of the Prelude movement alone end up in other people's hands?

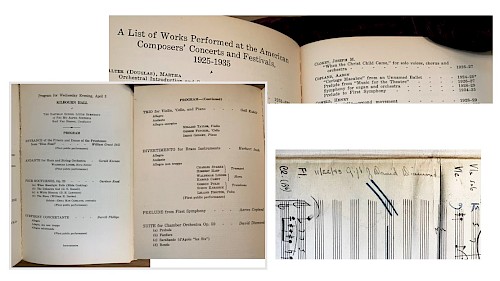

Arthur Berger's mid-century book on Copland raised further questions about the Prelude for Chamber Orchestra, which is included in the book’s list of Copland's works. Surprisingly, he indicates it was published in Musical Mercury magazine in 1935. But this contradicted the records of Boosey & Hawkes and the Copland Fund. Not only was Berger there at the time, but he was the editor of Musical Mercury and ought to know. Who was right?

Thanks to the amazing, digital repository of 19th and 20th-century music periodicals known as RIPM, I located the correct issue of this rare magazine—only to discover Berger's error. The score that appeared in Musical Mercury was indeed Prelude, but it was the large orchestra version. Musical Mercury in 1935 literally reprinted the first seven pages of the First Symphony score, which itself had been published just four years earlier. What was that about?

I found some fascinating answers. While they didn't shed much light on the piano trio arrangement, I did learn that Prelude was getting a lot of attention in the mid-30s in the New York City modern music scene. A short article in the Musical Mercury issue described the Prelude for Chamber Orchestra and the recently published First Symphony, noting their popularity and recent performances of both.

And I began to see what a small professional world encompassed Copland and his circles in 1934 and 1935. Berger was the editor of Musical Mercury. Musical Mercury was the house organ for Kalmus Music Publishers. Copland's First Symphony had been published (1931) by Cos Cob Press, a non-profit subsidiary of .... Kalmus.

Then I read that Copland made the Prelude for Chamber Orchestra for Bernard Herrmann, who conducted the premiere. Why was the film composer who scored Hitchcock's Psycho hanging out in Copland's modernist composer circles in New York City?

Answers were tangential to the piano trio, but illustrative of the interconnectedness of New York City's modernist music scene. Herrmann attended Juilliard. He had known Copland and Kirkpatrick for at least two years when he premiered Copland's chamber arrangement of Prelude. He, Berger, and Kirkpatrick attended informal gatherings at Copland's loft in the mid 1930s. Herrmann and Berger co-edited the first two issues of Musical Mercury together, in 1934. Once again, the takeaway was that Copland's social and professional circles were tight and that Prelude was part of those circles in 1934 and 1935.

When I went to see the manuscript for the chamber arrangement at Eastman, I learned more about why it landed in Rochester, rather than in the Aaron Copland Collection.

David Diamond had donated the manuscript to the library at Eastman in 1943. Where did he get it? Probably from Copland or Herrmann. In the summer of 1934, the young Diamond (1915-2005) moved from his family's home in Rochester to New York City to study composition. The following April, Copland's chamber arrangement preceded a work by Diamond on a concert that was part of Howard Hanson's 5th Festival of American Music in Rochester. The chamber Prelude dropped out of sight until Diamond's 1943 donation. It wasn't until the 1960s that Boosey & Hawkes (by then Copland's exclusive publisher) got Copland's permission to publish Prelude for Chamber Orchestra.

Back to the Date Question

Prelude for Chamber Orchestra and Prelude for Piano Trio have much in common: the notes, phrases, harmonies, etc. (both are arrangements Copland made of the Organ Symphony's first movement alone); both manuscripts ended up in other people's hands and were lost or forgotten for a while. Perhaps they have a date in common, too? Were both of them part of the mid-1930s revival of interest in the orchestral Prelude movement?

I went back to compare the title pages of the two neglected manuscripts. In contrast to his 1934 chamber orchestra arrangement (on the left), Copland didn't date the trio manuscript.

| Version for Chamber Orchestra | Version for Piano Trio |

|  |

| Eastman School of Music, Sibley Music Library | John Kirkpatrick Papers, Yale Music Library |

But I noticed something else about the two title pages. Copland wrote "from the First Symphony" on one (left), but "from the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra" on the other. Could that indicate that the piano trio arrangement preceded the First Symphony? The First Symphony was published in 1931 but arranged during the years 1926-1928.

And I notice that the paper and the handwriting look quite different. Physical clues—the type of pen or pencil, the brand or age of the manuscript paper Copland used in each instance—might help. I begin to understand why "old-school" musicologists drone on sometimes about worm holes, watermarks and ink.

Belatedly, I find a relevant morsel in Pollack's 1999 Copland biography, which is remarkably thorough on instances of Copland's self-borrowing. In the pages about the Organ Symphony, I learn that the Prelude theme also appears near the end of Copland's Movement for string quartet. Movement is an early work (1923-24) that was rediscovered and published decades later.

Now there is a fifth instance of Prelude's opening theme to account for! More date questions arise. Which came first: the string quartet, the Organ Symphony movement, or the Prelude for Piano Trio? Or was there an even earlier sixth instance, now lost, scrawled on a scrap of paper in a Parisian café?

Further sleuthing in the various archives could, theoretically, answer some of these questions. I could stumble upon a dated sketch, or piano score bearing the octatonic theme. An early letter may surface referencing the trio. Perhaps an associate of Copland or Kirkpatrick—a violinist or cellist?—wondered, in writing, if Copland had any piano trios besides Vitebsk that they could perform. But searching for possible mentions of a short, little-known piano trio in a letter between every likely combination of Copland associates over a 20-year time span seems a Sisyphean project.

Why Did He Lose Track of Both Arrangements?

I won't stop the search. But for now, I turn to a question with more room for interpretation. Why did both Prelude-only manuscripts end up in other people's hands? I suspect he lost track of them, amidst a sea change in his views about the proper audience for new American music. Copland and his circles engaged in an intense—and politically informed—re-examination of their aesthetic outlook in 1934 and 1935. Copland emerged from that period with a musical language heavily influenced by North American folk melodies. El Salón México (1936) and Billy The Kid (1937-38) were the first orchestral products. They made him famous to a broad swath of concertgoers. Copland's new direction was so fruitful—and kept him so busy—that chasing down arrangements of a ten-year-old modernist symphonic movement, even one he liked, was simply not a priority.

Seen in this light, the Prelude arrangements became points on a road not taken. The publications of the 1960s show that he was happy to revisit that road later in life, once his compositional pace had relaxed.

At least, that's my current answer to the "why did the Prelude arrangements languish" question, but I reserve the right to adjust my conclusion as new evidence emerges. Let's hope whatever it is answers more questions than it raises.

Sources & Further Reading

- Berger, Arthur. Aaron Copland. New York: Oxford University Press, 1953.

- daviddiamond.org accessed 9 July 2023.

- DeLapp-Birkett, Jennifer. “Aaron Copland’s Elusive Prelude for Piano Trio.” Paper presented at the AMS Capital Chapter Meeting [online], 21 October 2023.

- John Kirkpatrick Papers, Irving S. Gilmore Music Library, Yale University.

- Massey, Drew. John Kirkpatrick, American Music, and the Printed Page. Eastman Studies in Music, 98. Rochester, NY, Boydell & Brewer, 2013.

- Perlis, Vivian and Aaron Copland. The Complete Copland. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013.

- Perlis, Vivian. "Aaron Copland and John Kirkpatrick." In Copland Connotations, ed. Peter Dickinson (Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer, 2002), 57-65.

- Pollack, Howard. Aaron Copland: The Life & Work of an Uncommon Man. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1999.

- Smith, Steven. A Heart at Fire's Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

- Special Collections, Sibley Library, Eastman School of Music.