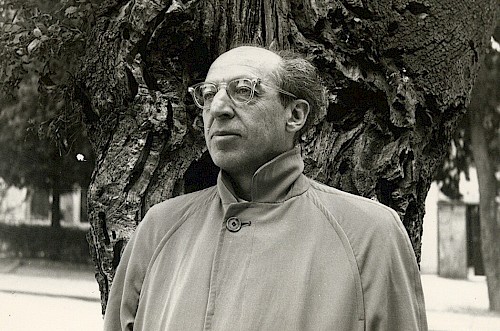

Copland is the composer whose music, writings, and biography I know best. As a result, I find resonances with Copland in many of my music-related experiences. Concerts, program notes, articles, history, philosophy, trends, human relationships, the act of writing a letter...many of these will bring to mind something Copland did, said, or composed.

Earlier this fall, Ronit Seter, a musicologist friend whose specialty is Israeli art music, invited me to one of the gatherings she has been hosting for years. Formerly held at her home in Virginia, these meetings moved to Zoom in 2020, allowing geographically scattered participants to attend. The focus of this "Salon Seter" was to be Shulamit Ran, the acclaimed composer with whom Seter is collaborating on a biography. Ran herself would join the call partway through.

The chosen date was Sunday, October 8—the day after the Hamas terror attacks on Israel. Out of ten or eleven participants, three were connecting directly from Israel. Three others had immediate relatives or dear friends who were suddenly in a war zone. We discussed whether to postpone, but the consensus emerged that even those most directly affected welcomed a reprieve from the constant news cycle. Of course, if a siren sounded, they'd have to sign off.

Before Ran joined the call, we reviewed her biography. Known as "a pillar of the Windy City's classical scene as a composer, teacher, and tireless advocate for new music” (Kyle Macmillan), she was a professor of composition at the University of Chicago from 1973 until her retirement in 2015. In 1991, she won a Pulitzer Prize for Symphony; she was the second woman to do so since Ellen Taafe Zwillich in 1983. She served as composer in residence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1990-97) and the Lyric Opera (1994-97), and holds memberships in the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Her works have been performed by many leading ensembles in the U.S., Europe, and Israel.

After Ran came on line, Seter interviewed her, and we listened together to excerpts from what Seter has dubbed Ran's "Israeli cycle." Written between 1987 and 2000, these five works—East Wind, Vistas, Mirage, Legends, and Voices - feature Eastern (Mizrahi) musical motives and readily audible tonal centers. The wide variety in the sound of Ran's works is illustrated well by comparing those works to Moon Songs (2012), to her first opera, Between Two Worlds (The Dybbuk) (1997) and to Credo (2006)—commissioned by the choral group Chanticleer as a movement for a modern Mass cycle.

We didn't talk about Copland at all, and we shouldn't have. But to my Copland-saturated mind, resonances abounded.

Setting and purpose

The first resonance was the setting itself: an informal gathering of friends with a shared interest in contemporary "classical" music—in our case, mostly musicologists, but also music librarians, music educators and composers. Copland hosted many such gatherings in his apartment in the 1930s and onwards. Friends and colleagues would share newly written or rediscovered music, introduce each other to new composers and performers, or discuss and debate trends in their field. In his twenties, he had attended "salons" in Paris and New York, where artists, writers, patrons and musicians met at the apartments of, for example, Nadia Boulanger or Paul Rosenfeld.

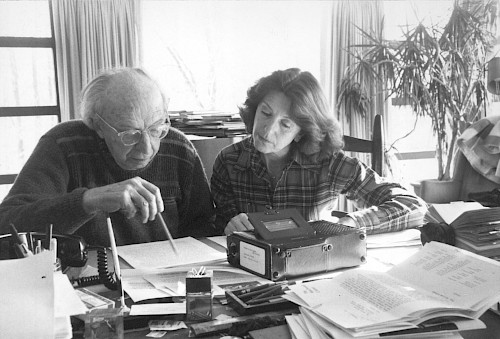

A second resonance was the purpose of our meeting. The October gathering was a warm-up to a week of in-person interviews that Ran and Seter had planned over the summer. The two have been acquainted for nearly twenty years: earlier interviews and much correspondence lay behind the 70-page chapter about Ran in Seter's 2004 dissertation. Only when Ran had completed her Anne Frank opera (December 2022) did the time seem right to embark on a full-blown biographical project. Similarly, but fifty years earlier, musicologist Vivian Perlis had already been interviewing Copland for two years when the idea of an autobiography emerged, leading eventually to Copland 1900-1942 (St. Martin’s-Marek, 1984) and Copland since 1943 (St. Martins, 1989) Copland and Perlis, and now Ran and Seter, engaged in a project of summation and reflection - composer and musicologist creating a narrative for posterity.

Similarities and differences

As composers, Shulamit Ran and Aaron Copland are not obvious parallels. They may share U.S. residency, Jewish heritage, and the so-called "art music" tradition: contemporary music written for performance primarily by European orchestral instruments, usually in concert halls. But they differ in generation, gender, training, life experiences, personal style, and career trajectories. And one would never confuse any of their music for the other's.

While Ran's career unfolded during the time she served on the faculty of a single university, Copland never accepted a permanent position in the academy. (He held a small number of visiting professorships and taught at Tanglewood many summers.) Ran, who began her career as a concert pianist, has limited her subsequent professional activity to composition. In addition to composing, Copland is also well-known as a writer on music, a cultural ambassador for the U.S., and for conducting. Ran was born in Israel and came to the US as a teen prodigy, where she continued the compositional studies she had begun in Israel. Copland was born in Brooklyn and moved to Paris as a young adult for his musical training before returning to the U.S. to begin his career.

The generational difference of almost 50 years between Copland and Ran affects not only their biographies but also the compositional trends that surrounded them. When Copland studied in Europe in the 1920s, atonal music was just emerging. By the time Ran was born, after World War II, atonality had permeated the Western world, had been challenged in many countries by a resurgence of nationalism (including Copland's populist American works), and had returned full force to the point where it seemed that any "serious" composer was suspect if he or she wrote music with a hummable tune. "Free atonality" with "rapidly changing tonal centers" describes Ran's music well into the 1980s.

After I investigated further, I discovered that the careers of these two composers have some small similarities, and even one direct interaction. Their reputations as composers were first established outside the academy. Neither earned a doctoral degree in composition, though both were awarded numerous honorary degrees. Of the composers teaching at Tanglewood when Ran attended as a teenager, "the music I wrote was probably most in sync with Copland," she told Seter in 2002. After I played for him my Sonata [No. 2, 1962], he said—I will never forget his exact words: 'You have no problems. You’ve got it all solved! What are you coming [to me] for?' He understood that there was no need to 'mold' me at that point in time..."

Gratitude and satisfaction

Given the preponderance of differences, I was surprised when, as Ran spoke on October 8, a deep resonance with Copland emerged: satisfaction and gratitude for a life devoted to music. Despite the unfolding war in her homeland, Ms. Ran spoke with peace and conviction, grace and intelligence. Among other things, she described her criteria for choosing composition projects: She never accepted a project, she said, unless she fully believed it was personally meaningful and had larger significance. Looking back on her long career, she expressed the belief that every work she had completed was "just what it needed to be."

Copland's words sprang to mind, as they appear in "Reflections on my Life in Music," an essay found in The Complete Copland. "As I see it, being a composer is a great privilege," he told Perlis in 1977. "I find a profound satisfaction in the fact that the works I composed in my own home have found a response in the outside world.... It has been my good fortune to spend my life with the art of music."

Likewise, being a composer has brought Ran a sense of significance and meaning that surpasses any other passion or activity. "I cannot imagine myself not a composer," she told me in a follow-up call on December 6. "Certainly, as the years go by, I feel more and more cognizant of that fact, and grateful."

National identities and "style change"

More generally, Seter and I have long discussed a broader parallel between the search Copland and his colleagues undertook in the 1930s for an American sound, and Israeli composers' pursuit of a national music that would speak to the modern identity of Israel after 1947; this is one subject treated at length in Seter's 2014 Musical Quarterly article. Applied to Copland and Ran, questions of national identification and musical style can raise many difficult issues concerning collective and individual cultural identity, colonialism, capitalism, antisemitism, and democracy (see Levin, Pollack, Seter and others).

Both Copland and Ran have been described as shifting from writing modernist, atonal music early in their careers toward a more accessible, tonal style that incorporated their respective national identities. Seter writes (2004) "Whereas Ran had built her early reputation ... on a style deriving from the Second Viennese School and its American counterparts, during the 1990s she was ready to reveal her Israeli roots and devoted several compositions to exploring the Israeli motif she had absorbed as a child..." Copland himself described his search for an American sound in the 1930s, which led him to what he called an "imposed simplicity" that drew from American folk tunes.

Yet both composers also protest the implication that their musical changes were abrupt or artificial, emphasizing instead continuity and consistency. Ran agrees that her "Israeli cycle" does mark a return to her roots, but she points out that Jewish-Israeli concerns were already present in her 1969 work O, the Chimneys! Asked on October 8th about her "changing style," Ran replied, "I like the term 'musical language' better than 'style'—one's individual voice."

Her correction immediately made me think of Copland's response in 1950 to an interviewer who asked whether audiences would appreciate the Second Viennese-influenced dissonance of his new Piano Quartet: "Music lovers who are used to hearing new works would expect a certain kind of musical language addressed to them. It’s like words that you use. If you’re talking to somebody who hasn’t had a college education you’re a little wary of using words he or she might not understand. But you wouldn’t necessarily change your thought."

Music, tragedy, and meaning

Both composers acknowledge that words and music express something more meaningful than sounds or words. And that a finished work of art is deeply meaningful not only for the composer, but by extension for a broader community.

Copland wrote, "Music is a world of the emotions, feelings, reactions. The language of music exists to say something—not something that can be translated into words necessarily, but something that constitutes essential emotions that are seized and shaped into meaningful forms. I wouldn't want to translate it into so many words because that would be limiting it. The feelings are like feelings are—emotional, and sometimes sort of vague. It shouldn't always be possible to put them into words.” (Composers Voices, 328)

Ran and Copland both describe the products of their efforts as personal, internal, and true. By composing, Copland said, "An artist can take his personal sadness or his fear or his anger or his joy and crystallize it, giving it a life of its own. ... It is the only place where a man [or woman] can be completely honest, where we can say whatever is in our hearts or minds, where we never need to hide from ourselves or from others." (Composers Voices, 328)

Ran affirmed the significance of every work she has written, a view she credited to her mentor Ralph Shapey. "I don't take on any project unless I can believe in it fully. Every work has to be right for itself," she said. And Copland wrote that in order to compose, "you do have to be truly convinced about the value of what you are doing. [...] You really must be brave, but the bravery is derived from inner conviction." (Complete Copland 78b).

Both composers also stressed the communal, life-affirming, life expanding qualities of the act of composing. "I think that my music, even when it sounds tragic, is a confirmation of life, of the importance of life," Copland told Perlis. "[W]hen I listen to a great work by [another composer], I have a larger sense of what it means to be alive." He continued, "Art summarizes the most basic feelings about being alive. It is very attractive to set down some sort of permanent statement so that people will be able to go to our artworks to see what it was like to be alive in our time and place—twentieth-century America." (Composers Voices, 329).

Ran has said "I believe that art is, above all, an expression of our humanity." (Seter 2004). Her String Quartet No. 3 was inspired by the work of a Jewish painter, Felix Nussbaum, who died in Auschwitz in 1944. "I ... try to place myself in the mind and the heart of an artist working during such an era, with his own life in peril and knowing that he may very well be facing death, and yet having this great desire to pursue his art, to continue creating. By keeping these memories alive you do fight back. You honor and you go ahead." (Ran & Pacifica, 2020)

As the Zoom Salon ended on the afternoon of October 8, I was moved by the thought that music in times of tragedy and even terror is not an escape from reality. It can reclaim and honor humanity—a shared humanity. Copland and Ran remind us that musical art is a meaningful human response to goodness and to grief. Two composers from very different vantage points, when reflecting on their life's work and the value of their art, are not so different after all.

Sources & Further Reading

- Copland, Aaron. "From audio and video interviews with Vivian Perlis, 23 December 1975 to 24 June 1978, Peekskill, New York." In Vivian Perlis and Libby Van Cleve, Composers' Voices from Ives to Ellington: An Oral History of American Music. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), pp. 300-329.

- Copland, Aaron. Interview with Pearson Underwood, October 30, 1950. Audio tape in the Library of Congress Recorded Sound Collection.

- Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. “Reflections on My Life in Music.” In The Complete Copland. (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013), pp. 340-341.

- Levin, Neil W. "Aaron Copland." https://www.milkenarchive.org/artists/view/aaron-copland Accessed 27 November 2023.

- Levin, Neil W. "Shulamit Ran." https://www.milkenarchive.org/artists/view/shulamit-ran Accessed 27 November 2023.

- MacMillan, Kyle. “Composer Shulamit Ran Stands Tall Among a Class of Towering Talents.” July 03, 2023. Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association, Experience magazine. https://cso.org/experience/article/14409/composer-shulamit-ran-stands-tall-among-a-cla Accessed 30 November 2023.

- Pollack, Howard. "Copland and the Prophetic Voice." In Oja, Carol J., and Judith Tick, eds. Aaron Copland and His World. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 1-14.

- Ran, Shulamit. Audio-video interview by Neil W. Levin for the Milken Archive Oral History Project [19 August, 1997]. https://www.milkenarchive.org/oral-history/view/ran-shulamit. Accessed 1 December 2023.

- Ran, Shulamit and Pacifica Quartet. "Pacifica Quartet and Shulamit Ran present Glitter, Doom, Shards, Memory [String Quartet No. 3]." Video discussion with music examples. Posted 26 June 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cxb7B8vDBtM Accessed 4 December 2023.

- Seter, Ronit. “Israeli Art Music: Shulamit Ran” in Oxford Bibliographies Online. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199757824/obo-9780199757824-0264.xml#obo-9780199757824-0264-div2-0031. Accessed 30 November 2023.

- Seter, Ronit. "Israelism: Nationalism, Orientalism, and the Israeli Five." Musical Quarterly 97:2 (Summer 2014): 238-308. https://doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdu010

- Seter, Ronit. “Shulamit Ran: Between Two Worlds: Mirage of Tel-Aviv in Frosty Chicago; Or, How Viennese Expressionism Merged with ‘Israelism’ in American Compositions.” Chapter 6 in “Yuvalim be-Israel: Nationalism in Jewish-Israeli Art Music, 1940-2000.” (Ph.D. diss., Cornell University, 2004), pp. 375-453.