The arc of the Piano Concerto's reception is familiar. It began with a succès de scandal in the Roaring Twenties, enjoyed a revival under Bernstein in postwar decades, and gradually faded into "lesser known" status by the end of the 20th century. Today, it remains in public view due to 21st-century champions including Michael Tilson Thomas and Paul Lewis, and several highly regarded recordings.

With nearly 100 years of performance history to consider, the work’s reputation cannot be summed up in a single statement. Yet it seems fair to say that performances with the strongest impact are those that first, capture Copland's attitude and performance style, and second, convey the work's distinctly American approach to rhythm. Given those conditions, whether the impact is strongly positive, or strongly negative depends on a third factor: listener expectations.

There are three general phases to consider in the performance history and reception of the Piano Concerto: (1) the scandalous performances of the first twenty years (1927-1947); (2) the midcentury revivals with Leonard Bernstein, Leo Smit, and Copland (1947-1960s); and (3) programming to celebrate milestone birthdays and anniversaries later in Copland’s lifetime and beyond.

The First 20 Years

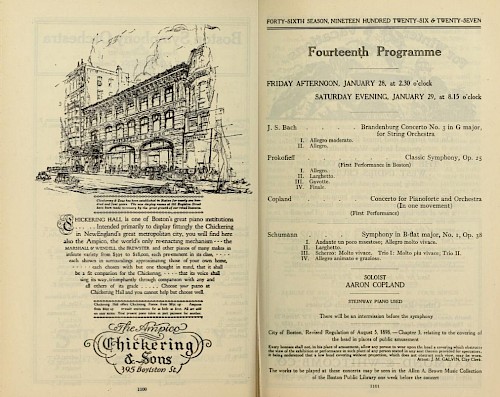

At the premiere in 1927, infamously, audience members hissed; some stood up and left. According to the Boston Globe, "the audience forgot its manners, exchang[ed] scathing verbal comments" and created a scene unparalleled in 15 years. The Boston papers published many complaints from audience members offended enough to write the editors. The Piano Concerto made one Boston listener envision "a dance hall next door to a poultry yard." Another thought it disparaged American cities as 'nervous, irrelevant, and pitched almost to a scream.’” (Complete Copland, 56; Pollack, 157).

Less colorfully, the Boston Herald critic wrote "Copland's Piano Concerto shows a shocking lack of taste. . ." The piano seemed to be "struck by fingers . . . at random." A Boston-based friend of Copland named Nicholas Slonimsky, the future author of the Lexicon of Musical Invective, clipped all the printed insults he could find and sent them to Copland afterward.

When the Boston Symphony Orchestra gave the New York premiere the next month, the reception was similar. But two positive responses stood out to Copland. The Herald Tribune praised the concerto as "music of impressive austerity, of true character, music bold in outline and of singular character." (Lawrence Gilman, Complete Copland 56-57). Perhaps with an element of hometown pride, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called it "the most excellent of symphonic jazz expressions." "Mr. Copland has quite outdone Mr. Gershwin and Mr. Carpenter," the critic continued, implying that Gershwin's 1924 Rhapsody in Blue and two jazz-influenced works by John Alden Carpenter, the Concertino for Piano and Orchestra (1917) and Krazy Kat ballet (1922), lacked Copland's bold, forward-looking, modernist flavor.

Early audiences for Copland's Piano Concerto were clearly expecting something different. The concert-hall establishment was dominated by European composers, with a sprinkling of older, conservative Americans like John Knowles Payne or Carpenter. In rare cases when American orchestras played modernist music, it was by famous Europeans like Stravinsky. If concert-goers in Boston or New York knew of symphonic jazz, it was George Gershwin and Paul Whiteman—what was considered "light" or "pops" music. Audiences were not expecting jazz-tinged modernist music from a Brooklyn-born, first-generation Jewish-American composer. One critic at the Boston premiere accused Koussevitzky of being a malicious foreigner who wanted to show how bad American music was! (Complete Copland, 56).

The scandalous reception extended far beyond New York and Boston, generating enduring anecdotes. At the Hollywood Bowl in 1928, Copland recalled, "'the musicians actually hissed. The conductor, Albert Coates, was distraught: 'Boys! Boys, please!' he pleaded pointing to me at the piano. 'He's one of us!' The Los Angeles Times reported: 'Bowl stirred up a frenzy. . . Fans greet sophisticated jazz with derision . . . catcalls, hisses, laughs and applause follow pianist. . .'” (Complete Copland, 62).

Midcentury Revivals

For many years (ca. 1933-1947) the Piano Concerto went unperformed in the U.S., but as Copland said, "retained its reputation as a 'shocker.'" (Complete Copland, 57). Just after the war ended, the 28-year-old Leonard Bernstein revived the work in a landmark New York performance—featuring, for the first time, a pianist other than Copland. By this time, much had changed in terms of audience expectations. Copland was by then known for popular Americanist-patriotic works like Billy The Kid, Rodeo, Appalachian Spring, and Fanfare for the Common Man. American music as a whole had also changed: jazz had developed, sound recording had taken off, and listeners could hear modern music of all kinds more easily.

Leo Smit later recalled, "The first time I heard the opening of the Piano Concerto, I thought of Moses blasting away on the mountaintop. How young he was and already filled with the confidence and the power of his own voice!" (Complete Copland, 265). Copland recalled the reviews: "no one could imagine why audiences in 1927 had walked out on it. . . the Concerto was called 'a relic of Le Jazz hot,' 'the nostalgic ghost of Paris's left bank,' and 'the best roar from the roaring twenties.'" (Complete Copland, 57) Copland's longtime friend, theater director and critic Harold Clurman, characterized the Concerto as "a gay acquiescence and even affirmation of the dervish ferocity of the world's mechanics." (Loggia & Young, 97-98).

Leo Smit gave several more performances in the next 10 years. With Copland conducting, he played the European premiere with the Radio Rome Symphony Orchestra in 1950; recorded by the Concert Hall label, it is still available today. In 1953, Copland and friends made much of Smit's performance with the Boston Symphony—the first in that city since the notorious premiere. In Copland's recollection, the performance lacked the ideal American flavor. "Leo garnered rave reviews, while Munch's conducting was called 'rectangular.' (After all, one would not expect the jazz rhythms to be in his bones any more than Koussevitzky's.)" (Complete Copland, 58). But the work did get more exposure under Munch's baton, as he played it in Brooklyn and Tanglewood later in the season, with Smit as soloist. Copland returned to the piano in 1958, playing it on August 7 at the Berkshire Music Festival with Richard Burgin conducting. Critic Harold Schonberg was tepid, calling it "a rather dated work, with its echoes of Gershwin and jazz of the Nineteen Twenties."

By the 1960s, American composition had splintered into such divergent directions that Copland's jazzy, dissonant Piano Concerto seemed tame indeed. Electronic sounds and numerically structured composition flourished in university music departments, while John Cage and others launched multi-media experimental artworks and "happenings" that deliberately included elements of chance and challenged the very definitions of music composition.

In 1961, fifteen years after Copland and Bernstein recorded the work, a second recording was released, this time with Copland on the podium and Earl Wild as pianist. Both recordings have endured, but Copland’s pianism is considered “more persuasive in the passages influenced by jazz.” (Penguin Record Guide, 1991)

Bernstein remained an important champion of Copland's Piano Concerto. Conductor of the New York Philharmonic, composer of the Broadway hit West Side Story (1957), and a photogenic TV personality, his multiple platforms were large. Not only did he include the concerto in a televised Young People's Concert, but he placed it in a five-concert New York Philharmonic series exploring avant-garde trends. In 1965, a Bernstein performance with Copland at the piano was released by Columbia, a recording still regarded sixty years later as one of the three best by many critics, who remark that Copland's personal performance style and Bernstein's intuitive grasp of Copland's intent perfectly capture the jazziness, rhythmic interplay, and ebullience of the composition.

Copland conducted the Piano Concerto several times in the 60s and 70s—including at the Hollywood Bowl in 1967 and in 1970 with London Symphony Orchestra—with mixed reception. Whether critics felt the work was successful or not, reviews of these performances and recordings often included some historical perspective, noting the work's scandalous initial reception with some surprise, and acknowledging its early and unique approach to the blending of jazz and symphonic music.

The Past 50 Years

From 1980 through the Copland centenary in 2000-2001, performances of the concerto were often ceremonial and celebratory, suited to Copland's cultural stature as a beloved senior member of the Great Americans of the Twentieth Century club. Of several performances in the nation's capital, the most notable was an 80th birthday concert at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. Copland conducted the National Symphony with Smit as pianist, while Bernstein—who conducted Lincoln Portrait that night with Copland narrating—helped rehearse it. Five years later, Bennett Lerner played it with Zubin Mehta in New York for Copland's 85th birthday.

In the 1990s, two younger musicians emerged as champions of the work: conductor Michael Tilson Thomas and pianist Garrick Ohlsson. Their recording of the work with the San Francisco Symphony on a release titled Copland the Modernist (RCA Red Seal, 1996) garnered much good publicity. "Copland the Modernist is every bit as great a composer as Copland the Populist," raved James Leonard in AllMusic. “With virtuoso pianist Garrick Ohlsson on the Piano Concerto, Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco perform Copland’s vulgar, cerebral, harsh, and complex music with ease, assurance, and extraordinary panache, making it sound as brilliant, as beautiful, and as endearing as any of his later Populist music."

Grammophone's critic Edward Seckerson heard incredible excitement in the Ohlsson/Tilson Thomas recording. It reminded him of Bernstein's 1944 On the Town: "concert jazz with attitude, sinewy, street-smart, strident, dislocated, blowsy, bumping, grinding, shimmying. . .” He marveled that Copland’s concerto predated On the Town by nearly 20 years. At the older work’s premiere, "Middle America (which had mentally drawn a line under Gershwin in that regard) was taken aback—temporarily." The critic then described his own listening experience. The concerto’s opening was "audacious enough to subdue the MGM lion on the opening gambit stakes. A bold proclamation passed between trumpets and trombones, a ‘fanfare for . . .’; but before you can finish the sentence, a dramatic cut to the wide shot: a glorious lyric effusion, its sights set on yet another gleaming skyline. Brave new world or lonely town? The quizzical solo piano isn’t entirely sure, but the yearning grows [. . .] as muted clarinets take us in deeper, and deeper, the piano player shucks the cigarette, flicks the wrist, mindful of something snappy; snappy, as in fractured and slightly tipsy."

Ohlsson performed it many more times across almost two decades: in May 1999 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by John Adams; in 2000 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Andre Previn; and in May 2004 with the New York Philharmonic, conducted by David Robertson. He performed it twice in 2013 (once with Marin Alsop and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and once with Michael Stern and the Kansas City Symphony); in 2016 in Detroit under Leonard Slatkin and again in 2017 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood.

After his 1996 recording, Tilson Thomas teamed up with different pianists, including Jeffery Kahane (2003) and Jeremy Denk (New World Symphony, 2010). In 2016 the San Francisco Symphony brought the Piano Concerto to Carnegie Hall with Inon Barnatan as soloist, who, in addition to the performances with Tilson Thomas, had played it with Steven Jaarvi in St. Louis (2015), and would repeat it in San Diego (Andrew Gourley) later in 2016. The Barnatan/San Francisco performances earned particularly enthusiastic reviews. At the “compelling” pre-tour performance in San Francisco, critic Mayumi Wardrop (Bachtrack.com, 02 April 2016) described "the delight of watching Barnatan’s hands effortlessly navigating the rhythmic exuberance of the piece” and wrote that he was "clearly enjoying himself in the ragtime snappy bounciness.” When critic Anthony Tommasini reviewed the subsequent performance in Carnegie Hall, he praised both the performance and the composition: “It was a treat to hear the brilliant pianist Inon Barnatan as the soloist in Copland’s inexplicably neglected 1926 Piano Concerto, a piece steeped in jazz and written in two movements, with a dreamy Andante that segues into a feisty, propulsive Allegro." (New York Times, 15 April 2016).

Capturing Copland's Style

In keeping with Copland’s anti-Romantic sensibilities, Ben Pasternak’s performance with the Elgin Symphony Orchestra captured something Coplandesque that inspired reviewers to embrace the piece itself. Pasternack seems particularly gifted at conveying Copland's "crystalline" composer's touch, presenting the piano as a single, distinct tone color contrasting with the orchestral pallet. The Chicago Daily Herald called the recording "one of those discs that lovers of classical music (and Copland in particular) will return to time and again” while the Courier Post Online wrote “The conductor and his orchestra catch the jaunty, jazzy charm . . . Pasternack revels in the bluesy opening movement and sounds comfortable in the jazz-flavored second movement." The energy conveyed in the Elgin performance shines in Dan Morgan’s review in Musicweb international: The concerto "doesn’t have [Gershwin's] Broadway-inspired razzamatazz but what it does have is a more sophisticated, cosmopolitan feel . . . The insouciant, bluesy first movement—introduced with the usual fanfare—has the pianist doodling quietly at the keyboard. Benjamin Pasternack captures the languor of this movement very well indeed, the piano ideally placed and faithfully recorded. . . Copland’s detailed scoring is wonderfully realised too, the more expansive moments thrillingly intense but never overheated. . . Pasternack is suitably foot-stompin’ in those repeated jazzy phrases." For Morgan’s ears, this made the piece itself convincing and relevant, not dated in the least: "there is a fresh, individual quality to this concerto.”

Most recently, pianist Paul Lewis has given well-received performances in the UK in 2023 and at Tanglewood in July 2024. In a review for Bachtrack, Kevin Wells deemed the July 2024 performance and Copland's composition quite convincing, suggesting that Paul Lewis bested Copland himself. On the Copland/Bernstein recording, “[Copland’s] playing, . . . betrays a certain reserve, as if he’s pulling his punches. Paul Lewis, on the other hand, leaned in with gusto, letting the jazz swing and the blues wail. The riot of ragtime syncopation in the second movement was thrilling and the ease with which he navigated the gnarly rhythms of the cadenza a lesson in clarity and precision. He and the orchestra fed off each other in a performance that made one wonder why it took so long for this piece to make its mark."

Likewise, Chris Sallon in Seen and Heard International wrote, ". . . this inexplicably neglected concerto’s combination of symphonic modernism, jazzy riffs and ragtime rhythms were as zippy and energetic as they were almost 90 years ago . . . In the opening movement Lewis effectively evoked the smoky blues world of Jelly Roll Morton and early Duke Ellington, while the syncopated passages in the high-voltage second movement were executed with diamond tipped accuracy, and brilliantly co-ordinated with the orchestra."

Joseph Dalton in Albany’s Times Union was less enthused about the piece: Copland's "characteristic orchestral palate—the blues, jazz and big city grind—is all there, but his knack at a seemingly effortless form hadn’t arrived yet . . . Missing is much sense of balance and dialogue between soloist and ensemble . . . Maestro Andris Nelsons looked bored all afternoon but maybe that was just fatigue. This was his third concert of the weekend." Dalton apparently missed the Saturday morning run-through, open to the public, which to my own ears was even livelier than the Sunday performance.

Conclusion

The Piano Concerto utterly confounded listener expectations for a piano concerto in 1927. In the mid-century decades, as Copland's personal style and jazz idioms in general became more familiar on both sides of the Atlantic (and beyond), performers gained greater ease with the work. As a variety of Copland's music began to circulate, and both jazz and modernist music changed and expanded, listener expectations became less narrow.

The 1990s and 2000s are an interesting case though, because listeners had a different kind of bias. True, they were accustomed to musical modernism (even if they didn't like it). But their expectations for Copland’s music had been categorically altered by the ubiquity of the patriotic and accessible works he composed in the decades following the Piano Concerto. Audience members who expected folk-inspired Americana were surprised and sometimes disappointed by the concerto's disjointed rhythms and modernist sounds. Yet throughout these shifts in audience perception, one constant remained: The best received performances of the Piano Concerto captured Copland's own performance style, his playful attitude, and his percussive, rhythmic approach to pianism.

In 2025, "piano concerto" can mean almost anything, and most listeners know Copland had a modernist side. This 21st century listener finds the work to hold a fresh combination of detached neoclassical wit, and bits of blues and syncopated dance music glued together with drama that can border on the bombastic. If the recent performance at Tanglewood is any indication, the new performance materials help the musicians navigate the work’s rhythmic complexities in the light-hearted spirit that Copland intended, paving the way for another revival.

Sources & Further Reading

Books

- Copland, Aaron and Vivian Perlis. The Complete Copland. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2013.

- Loggia, Marjorie and Glenn Young, eds., The Collected Works of Harold Clurman. NY: Applause Books, 1994.

- Pollack, Howard. Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. New York: Henry Holt, 1999.

Select Reviews

- Baxter, Robert. Review of Pasternak/Elgin CD, Naxos 8.559297. Courier Post Online. May 2008. Cited at https://www.amazon.com/Copland-Piano-Concerto-Tender-American/dp/B001716IVG

- Dalton, Joseph. "BSO lauds Tanglewood Founder with Musical Weekend." Albany Times Union. 29 July 2024.

- Gowen, Bill. Review of Pasternak/Elgin CD, Naxos 8.559297. The Chicago Daily Herald. May 2008. Cited at https://www.amazon.com/Copland-Piano-Concerto-Tender-American/dp/B001716IVG

- Morgan, Dan. Review of Pasternak/Elgin CD, Naxos 8.559297. Musicweb International. 8 July 2008. http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2008/july08/Copland_8559297.htm

- Sallon, Christopher. "Paul Lewis Reunites with the BSO at Tanglewood in Measured Mozart and Adrenaline-Charged Copland." Seen and Heard International. 2 August 2024.

- Schonberg, Harold C. "Annual Tanglewood on Parade Attracts Record Crowd of 14,588." New York Times. 8 August 1958.

- Seckerson, Edward. Review of "Copland the Modernist" CD. Grammophone. March 1997. https://www.gramophone.co.uk/review/copland-the-modernist

- Tommasini, Anthony. "Review: San Francisco Symphony at Carnegie Hall." New York Times. 15 April 2016.

- Wardrop, Mayumi. "Captivating Copland and Superb Schumann from Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony." Bachtrack. 2 April 2016. https://bachtrack.com/review-copland-tilson-thomas-san-francisco-symphony-march-2016

- Wells, Kevin. "Koussevitzky at 150: Tanglewood celebrates with James Lee, Copland, Thompson and Stravinsky." Bachtrack. 29 July 2024. https://bachtrack.com/review-boston-symphony-orchestra-nelson-lewis-tanglewood-july-2024